Introduction

Imagine walking through your potato field in late August, expecting a healthy harvest, only to find entire sections of plants wilted and dying. This nightmare scenario plays out for thousands of farmers each growing season. Potato wilt disease stands as one of agriculture's most destructive pathogens, capable of destroying your entire crop and contaminating your soil for years to come.

Understanding potato wilt disease is no longer optional for serious growers. This soil-borne threat affects potato production worldwide, causing yield losses that range from minor reductions to complete crop failure. What makes wilt disease particularly challenging is that it takes multiple forms, each requiring slightly different management approaches. The good news is that with proper knowledge and early intervention, you can significantly reduce your risk and protect your investment.

In this comprehensive guide, we'll walk through everything you need to know about identifying, preventing, and treating potato wilt disease. Whether you're managing a small garden plot or commercial acreage, these strategies will help you maintain healthy potatoes year after year.

What is Potato Wilt Disease and Why It Matters

Potato wilt is a complex disease involving both the aerial parts and the economically important tubers. The pathogens attack and colonize the vascular system, particularly the water-conducting elements of the plant. Wilt results when this system becomes blocked or is badly damaged-meaning upward movement of water through the plant stops.

There are three fundamentally different types of wilt affecting potatoes, caused by entirely unrelated pathogens, with different survival mechanisms and requiring different management responses. Identifying which type is threatening your particular field becomes the first line of defense.

Understatement has no place here when discussing the economic impact. Untreated wilt disease can reduce yields by 50 percent or cause total crop loss in severe situations. Beyond the immediate harvest loss, contaminated soil can remain problematic for five to six years after infection. This long-term soil degradation makes prevention infinitely more economical than attempting to manage the disease once it appears.

Identifying the Three Types of Potato Wilt

Success in managing potato wilt begins with accurate identification. Each wilt type presents unique characteristics that, once understood, become relatively straightforward to distinguish.

Bacterial Wilt: Ralstonia solanacearum

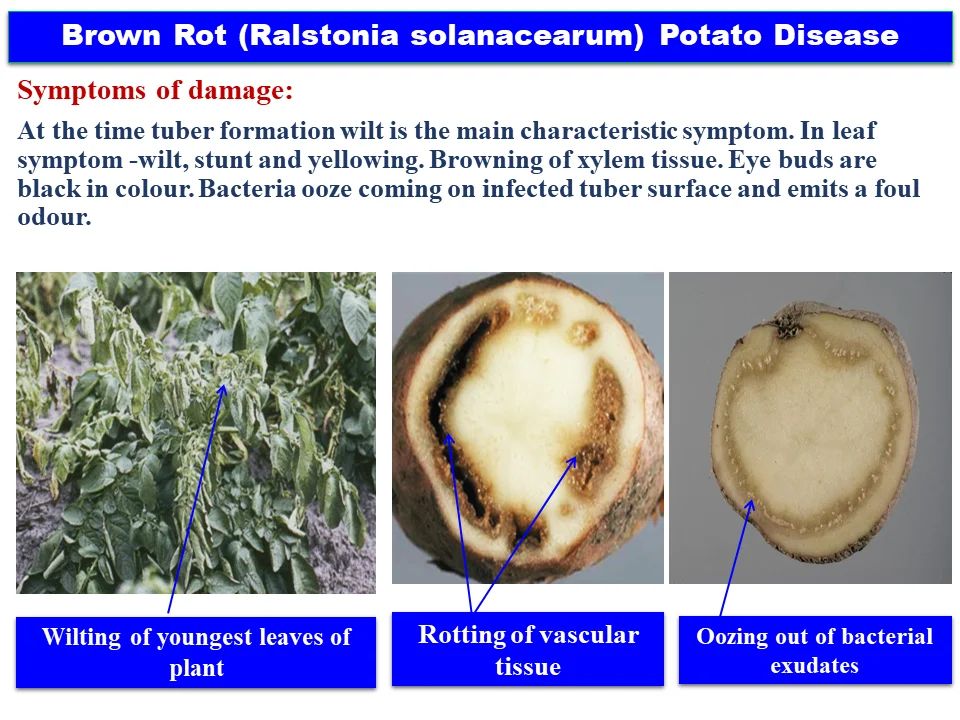

Bacterial wilt is caused by Ralstonia solanacearum, a soil-dwelling bacterium that represents the most destructive form of potato wilt in tropical and subtropical regions. This pathogen enters the plant through root injuries created by farm equipment, soil pests, or natural root cracks. Once inside, it multiplies rapidly in the water-conducting tissue, blocking water flow throughout the plant.

Above ground, bacterial wilt presents dramatic symptoms. Wilting appears first on lower leaves, giving the appearance of water-stressed plants. The wilted leaves roll upward and inward from their margins, creating a distinctive curled appearance. As the disease progresses, yellowing spreads upward along the stem, and affected leaves eventually turn brown and drop away. This progression occurs relatively quickly, sometimes within weeks.

Underground, bacterial wilt creates equally distinctive signs. Cross-sectioning infected tubers reveals vascular tissue with light brown to dark brown discoloration. The most telling symptom is the presence of bacterial ooze emerging from the tuber's vascular strands. In fresh tubers, this ooze appears as white, bubbly discharge. Over time, soil sticks to this bacterial mass, creating the symptom's alternate name "jammy eye," which resembles sticky, dirty eyes on the tuber.

Bacterial wilt thrives when soil temperatures exceed 85 degrees Fahrenheit combined with high soil moisture. Slightly infected tubers pose greater risk than obviously diseased ones because asymptomatic tubers spread the disease undetectably.

Fusarium Wilt: The Fungal Threat

Fusarium wilt is fundamentally a different challenge, this soil-borne fungus persists in the soil carrying its strains which specifically attack particular crops. However, it can also survive for years on organic debris without any living host and therefore once the disease gets established elimination becomes practically impossible.

The hallmark symptom of Fusarium wilt is gradual development. Unlike bacterial wilt's rapid onset, Fusarium symptoms take several weeks to appear. The disease usually begins with a wilting that occurs during the hottest hours of the day and temporarily recovers during the cooler hours of the evening and night. This condition persists for a few days before final permanent wilting sets in.

Fusarium infection creates distinctive leaf yellowing that often begins on one side of the plant before spreading throughout. The yellowing progresses upward as the fungus colonizes more vascular tissue. Leaves eventually brown and drop away. When stem tissue is split lengthwise, the interior reveals brown discoloration of the vascular system. This internal browning serves as the most reliable diagnostic indicator.

Fusarium prefers warmer soil temperatures between 80 to 90 degrees Fahrenheit, particularly in slightly acidic soil. Poor drainage, root damage from nematodes, and continuous planting of the same crops all increase Fusarium pressure. Once established in soil, the fungus can infect healthy plants through root wounds or direct root penetration.

Verticillium Wilt: The Persistent Pathogen

Verticillium wilt represents perhaps the most insidious threat because infected plants may show no visible symptoms while still harboring the pathogen. Two fungal species cause this disease: Verticillium dahliae and Verticillium albo-atrum, with dahliae being the more aggressive form.

Verticillium typically announces itself in late summer or early fall. The lower leaves gradually turn yellow and wilt, beginning the upward progression of symptoms. In some cases, only one side of a petiole wilts initially, a characteristic feature useful for distinguishing Verticillium from other wilt causes. The yellowing leaves eventually brown and drop, leaving stems erect rather than collapsing.

When infected stems are cut at the soil line, vascular tissue shows yellow discoloration that progresses to reddish brown. This internal streaking may extend through the entire stem and into the tuber. Infected tubers can develop brown or black discoloration in the vascular ring when viewed in cross-section.

The critical difference with Verticillium is persistence. The fungus produces microsclerotia, tiny resting bodies that can survive in soil for up to seven years without any host crop. These structures germinate when conditions become favorable, making field history crucial information for management decisions.

Early Detection: Your Most Powerful Tool

Early detection transforms wilt disease from a catastrophic threat into a manageable challenge. By identifying symptoms before disease becomes widespread, you can implement containment strategies that prevent field-wide infection.

Visual Symptom Checklist

Start your field scouting through organized visual observation. Look for the following major clues:

Lower leaf wilting that does not recover at cool times of the day (mostly Verticillium)

Yellowing moves upward from lower parts of stems

One-sided wilting on individual petioles

Brown discoloration evident when stems are split lengthwise

Premature leaf browning and drop

Stunted plants scattered among otherwise healthy plants

Distinctive smell emanating from diseased plants (especially bacterial wilt)

When Symptoms Typically Appear

Bacterial wilt: Symptoms progress rapidly once infection occurs, becoming visible within 2 to 4 weeks of root invasion.

Fusarium wilt: Slow symptom development means wilting may not appear until mid-season or later, and permanent wilting takes several weeks to establish.

Verticillium wilt: Late-season symptoms typically emerge in late August or September in temperate regions, though timing depends on soil moisture, temperature, and variety selection.

Field Scouting Strategy

Scout fields weekly during the growing season, walking transects across the field rather than just along field edges where disease might first appear. Early morning scouting, before heat stress makes healthy plants wilt temporarily, provides the clearest picture of actual disease presence.

In case you come across any suspicious plants, observe both above-ground symptoms and excavate the root system to see below-ground signs as well. In the case of a suspected bacterial wilt, smell the cut stem since the pathogen frequently produces characteristic odors. For final diagnoses in uncertain cases, take tissue samples to be checked in a laboratory through your regional agricultural extension office.

Leveraging Technology for Early Detection

Modern tools can enhance your detection abilities. Platforms like Plantlyze provide AI-powered plant diagnosis capabilities, allowing you to photograph suspicious plants and receive rapid preliminary assessments. These tools complement, rather than replace, your personal field observations. Technology works best when combined with your direct field knowledge and scouting experience.

Prevention Strategies: Your Best Investment

The farmer's adage "an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure" becomes literal truth with potato wilt disease. Because complete chemical cures don't exist and some diseases can persist in soil for years, prevention represents your most effective management strategy.

Pre-Planting Management

Before you even plant a seed potato, several crucial decisions set the foundation for disease-free crops.

Seed Selection and Treatment

Begin with disease-free seed potatoes from certified, reputable sources. Certified seed undergoes testing and certification specifically to verify freedom from major pathogens. This seemingly simple step prevents introducing the pathogen into previously clean fields.

If you save seed potatoes from your own harvest, inspect them rigorously and test plant tissue if any question exists about disease history. For fields with confirmed wilt disease history, certified seed becomes non-negotiable.

Hot water treatment provides an effective, organic-approved method for cleaning infected seed tubers. Exposing seed tubers to water heated to 122 degrees Fahrenheit for 30 minutes successfully kills Ralstonia solanacearum while maintaining seed viability. Some growers employ hot air treatment at 112 degrees Fahrenheit with 75 percent relative humidity for 30 minutes as an alternative approach.

Soil Testing and Field Assessment

Conduct soil testing through your agricultural extension office or commercial laboratory. Testing identifies nematode populations, which significantly increase wilt severity, and provides information about soil chemistry affecting disease risk.

Review the field's history carefully. Ask previous operators about any disease symptoms they observed. Fields with confirmed bacterial wilt history should not grow potatoes for 5 to 6 years. Fusarium-infested fields require rotation away from susceptible crops for 5 to 7 years. For Verticillium-infested fields, even longer rotations benefit because microsclerotia persist for years.

Resistant Variety Selection

Growing resistant varieties provides your most reliable long-term strategy when disease-free fields aren't available. Unfortunately, truly resistant potato varieties remain limited. Red Pearl represents the most reliable bacterial-wilt-resistant potato currently available, though availability and suitability for different production systems varies.

For Verticillium-infested fields, Russet Burbank has shown good tolerance to yield loss even when infected. Consult your extension office and seed providers for varieties with specific resistances matching your regional wilt threats.

Cultural and Environmental Management

These practices reduce disease pressure by creating unfavorable conditions for pathogens while removing potential infection sources.

Crop Rotation: The Foundation of Wilt Management

Crop rotation represents your single most powerful non-chemical tool. Rotating away from potatoes for 3 to 5 years dramatically reduces wilt pathogen populations. Every year you avoid planting potatoes allows existing fungal structures to decay and bacterial cells to die naturally.

Select rotation crops that don't host the specific wilt pathogens threatening your field. Corn, sorghum, wheat, and soybean will do fine in almost any region. Added to that is the green manure crop of legumes which also adds extra benefits to the soil structure. Do not rotate to other solanaceous crops such as tomato, pepper or eggplant since these are similarly susceptible to Ralstonia and some strains of Fusarium.

The more years you keep potatoes out of a field, the greater reduction in pathogens. Even one year provides some benefit that can be measured. Where field history is unknown or there are multiple threats from diseases, attempt to impose five-year rotations.

Moisture and Drainage Management

Both bacterial and fungal wilt pathogens are favored by wet soil conditions. Improving field drainage reduces these favorable conditions substantially. Install or improve drainage systems in chronically wet fields. Avoid planting potatoes in fields with poor natural drainage.

Adjust irrigation timing and amount to avoid creating persistently wet soil. Apply water early in the morning so foliage and top soil layers dry before evening. Use drip irrigation when possible to deliver water directly to root zones rather than wetting the entire field surface.

Monitor soil moisture with simple techniques like squeezing soil in your hand. If water runs from the squeezed soil, moisture levels are too high. Proper moisture supports growth without favoring disease.

Soil Temperature Management

Bacterial wilt becomes most virulent when soil temperatures go above 85°F. Where possible, adjust the planting schedule so that it does not coincide with peak summer temperature periods during critical infection stages. In some areas, a shift from spring to summer planting or spring to fall planting will be effective in imposing thermal stress on the pathogen during its optimal growth window.

Organic mulches cool the soil and at the same time retain water to create desirable conditions. However, ensure that the mulches do not remain perpetually wet because excessive moisture negates the benefit.

Biological and Organic Approaches

Beneficial organisms can suppress wilt pathogens, particularly when integrated with other management strategies.

Beneficial Microorganisms

Trichoderma harzianum and Trichoderma viride fungi actively suppress Fusarium in soil through direct competition and production of disease-fighting compounds. Pseudomonas fluorescens and Bacillus subtilis bacteria similarly suppress pathogenic fungi while promoting plant growth.

These beneficial organisms work best when established before pathogen populations explode. Apply biological control organisms to soil before planting, following product label directions. Ensure adequate soil moisture and temperature support beneficial organism survival.

Soil Solarization

For seriously infested fields, soil solarization uses clear plastic mulch to trap solar heat for 60 days, killing pathogenic spores and structures in the top soil layer. This technique works best in regions with strong, persistent sun and moderate rainfall. While solarization doesn't eliminate disease completely, it substantially reduces pathogen populations, giving newly planted crops a significant survival advantage.

Treatment Options When Prevention Fails

Despite best efforts, wilt disease sometimes establishes in fields. When this occurs, swift action minimizes the damage and prevents spread to additional areas.

Immediate Action When Disease Appears

The moment you confirm wilt disease presence, implement containment protocols.

Plant Removal and Destruction

Remove infected plants by pulling them entire, including roots. Place diseased plants in bags or containers to prevent soil from falling back onto the field. Transport diseased plants away from the field to a location where they can be buried at least one meter underground or composted at high temperatures.

Do not use diseased plants as animal feed or return them to fields as compost. The pathogens remain viable through normal composting temperatures.

Field Isolation

After working in an infected area, change clothing and thoroughly clean boots before moving to unaffected fields. Wash farm equipment in a designated area, not near other fields. This simple practice prevents carrying contaminated soil on equipment treads to clean fields.

Disinfect tools that contacted diseased plants with a 10 percent bleach solution or commercial disinfectant. Allow adequate drying time before using on healthy plants.

Irrigation Water Management

If you use irrigation from surface water sources, treat the water before applying to other fields. Chlorination or UV treatment eliminates the bacterial wilt pathogen from water. Never allow irrigation runoff from an infected field to flow toward clean fields.

Treatment Options Available

Unfortunately, once plants become symptomatic, complete recovery is impossible. However, managing remaining disease progression helps salvage remaining healthy plants.

Biological Treatments

For early disease detection, applying beneficial organisms like Trichoderma species or Pseudomonas fluorescens can suppress pathogen progression in remaining healthy plants. These treatments work best as preventive applications in uninfected areas of the field, not as rescue treatments for visibly diseased plants.

Apply these organisms according to label directions, ensuring good coverage of the soil zone and adequate moisture for organism establishment.

Chemical Control Reality

Complete truth: no chemical fungicides or bactericides cure bacterial or Fusarium wilt once symptoms appear. Some products delay symptom expression if applied before heavy infection occurs, but no chemical completely eliminates the pathogens.

Verticillium similarly lacks effective chemical controls. Fungicide applications during the symptom-free period might reduce severity slightly but won't prevent infection.

Acceptance and Field Planning

Once significant wilt disease establishes, acknowledge that crop loss will occur. Focus energy on preventing spread to other fields and planning the rotation sequence that will eventually make that field productive again. Document the situation for future reference and planning.

Long-Term Field Recovery

After confirmed wilt disease appearance, implement extended management protocols.

Crop Rotation Intensity

Plan for the extended rotations mentioned earlier: 5 to 6 years for bacterial wilt, 5 to 7 years for Fusarium, and up to 7 or more years for Verticillium. Use these years strategically to build soil health through green manure crops and organic matter additions.

Monitoring and Sanitation

During non-potato years, monitor the field for volunteers and other weeds. Tubers dropped by the harvesters or pickers can produce volunteer plants that will act as hosts to keep pathogens alive. Control nightshade, thorn apple, and other alternative host weeds.

Once the rotation period is over, use certified clean seed of a resistant variety accompanied by intensive management practices to minimize risk and reduce recurrence.

Practical Implementation Roadmap

Converting knowledge to action requires structured planning. Use this timeline to organize your wilt management program.

Pre-Season Planning (December to February)

Check field records for any past incidence of wilt. If you have recently acquired the land, contact the former operator and carry out a soil test through your extension office or commercial laboratory. In new fields or where no disease was observed in existing fields, order certified seed potatoes from reputed agencies.

Select varieties considering not only resistance to wilt but also your production requirements. Source resistant rootstocks if grafting production systems are suitable for your operation.

Early Spring Preparations (March to April)

Implement soil amendments identified through testing. Schedule equipment cleaning and disinfection. Prepare rotation plans for fields with disease history. Install or repair drainage systems in chronically wet areas.

Apply soil solarization plastic if using that technique, timing placement for adequate sun exposure before planting. Mix beneficial organisms with compost or farmyard manure if using biological control approaches.

During Growing Season (May to September)

Set a weekly schedule for field scouting. Walk the fields and observe any diseases systematically while recording other observations as well. Check the weather for any spells of high temperatures and humidity which would have favored the disease development.

Record infection locations to later use in forming better long-term management practices.

Do not let the field remain wet; apply irrigation based on moisture monitoring instead of following a fixed schedule. Monitor and control weed hosts and volunteer potato plants.

Harvest and Post-Harvest (September to November)

Before harvest, rake and burn potato vines from fields with disease history if your operation size allows. This removes potential pathogen sources returning to soil.

After harvest, collect and bury all diseased and discarded tubers separately from healthy produce. Never use diseased tubers as seed.

Thoroughly clean and disinfect all harvesting equipment. Document field observations for future season reference.

Real-World Impact and Farmer Experience

Statistics do not even begin to describe the actual devastation of wilt diseases. Here is a plausible scenario:

A commercial farmer with 50 acres under potatoes notices Verticillium wilt sometime in early August. The symptoms came late, and generally, the field looked healthy; thus, no disease was noticed during any mid-season scouting. By harvest time, about 35 percent of the field had shown severely stunted plants together with visible vascular discoloration. The yield loss amounted to about 20,000 bushels-approximately $35,000 in lost revenue. The field will sit in rotation for seven years before potatoes can be replanted. During those seven years, the grower will apply the integrated management practices outlined here.

Contrast this with a proactive grower who pulls three symptomatic plants in late July from the same field. Disease spread is limited to about 0.2 acres by practicing immediate removal, field isolation, and intensive late-season management. The field goes into rotation as intended but because the years of rotation are also practiced with aggressive pathogen suppression, the effect is that the risk level for wilt in the field when it returns to potato production is very much reduced. The total loss is several hundred dollars rather than tens of thousands.

This difference illustrates why early detection and rapid response merit your attention and investment.

Integrating Technology Into Your Management Plan

Modern tools can enhance your wilt disease management. Plantlyze and other AI-powered platforms are quickly redefining the speed at which a preliminary diagnosis can be made by analyzing images, giving results of whether it is wilt or any other disease. Combine this with your observation from the field; hence, slightly shorten that decision-making window.

Visit Plantlyze.com to access these AI-powered plant care and diagnosis capabilities. The platform helps you identify disease symptoms earlier and more confidently, enabling faster implementation of containment measures. Early identification transforms wilt management from reactive disaster control into proactive disease prevention.

Key Takeaways For Successful Wilt Management

Begin by clearly understanding that prevention dramatically outperforms treatment in effectiveness and cost long before an infestation starts to build up. Ensure proper identification of which wilt type threatens your fields because the responses are slightly different for each. Implement crop rotation as your foundation strategy, particularly for seriously affected fields.

Fourth, as far as possible and available, always use certified seeds that are free from diseases. Fifth, regularly scout or monitor the field during the cropping season so that any disease can be detected at an early stage before it spreads widely. Sixth, act fast when a disease has occurred; execute isolation and containment measures thereby restricting spread. Finally, accept that some situations require extended patience as fields recover through proper rotation sequences.

Potato wilt disease represents a serious threat, but one you can effectively manage with knowledge, persistence, and appropriate tools. Your successful harvest depends on the decisions you make today regarding prevention and early detection.

References

1. NIH/PubMed Central

Link: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4356456/

2. Nature Journal

Link: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-024-82272-3

3. UC Davis IPM (University of California)

Link: https://ipm.ucanr.edu/agriculture/potato/verticillium-wilt/

4. University of Maine Cooperative Extension

Link: https://extension.umaine.edu/publications/5041e/

5. APS (American Phytopathological Society)

Link: https://apsjournals.apsnet.org/doi/10.1094/PHYTO-12-18-0476-R