Introduction: When Your Potato Leaves Start Rolling Upward

Something is clearly wrong with your potato plants. The leaves are rolling upward at the edges, they've taken on a waxy, leathery texture, and the plants appear stunted compared to the rest of your field. You're looking at potato leafroll virus (PLRV), one of the most economically damaging viruses affecting potato production worldwide.

The damage goes beyond what you see in the field. Infected potatoes develop net necrosis, a browning of the vascular tissue inside tubers that renders them unsuitable for sale or use. An entire crop can be compromised, and if infected tubers are saved as seed, the problem replicates year after year.

The good news: PLRV is highly preventable. Understanding how the virus spreads, recognizing early symptoms, and implementing proper management strategies allows you to protect your crop effectively. This guide walks you through everything you need to know about identifying, preventing, and managing potato leafroll virus.

What Is Potato Leafroll Virus: The Basics

Potato leafroll virus belongs to a group of viruses transmitted exclusively by aphids. Unlike some potato viruses that spread through machinery or contact, PLRV requires a specific vector: the green peach aphid. This fact is both good and bad. Good because direct spread through contact isn't possible. Bad because aphids are difficult to control completely and can travel long distances, carrying the virus from field to field.

PLRV was historically the most serious insect-transmitted disease of potatoes in North America. While modern management practices and seed certification programs have dramatically reduced PLRV incidence in many regions, it remains a threat wherever potatoes are grown.

The virus is persistent in its aphid vectors, meaning once an aphid acquires the virus, it carries and transmits it for the rest of its life. This persistence makes PLRV particularly challenging to manage compared to non-persistent viruses that lose viability quickly after acquisition.

Recognizing PLRV Symptoms: What to Watch For

PLRV symptoms vary depending on when infection occurs and which potato variety is growing.

Chronic Infection: From Infected Seed

Plants grown from infected seed potatoes show the most severe symptoms. These plants are typically stunted and more erect than normal, growing with an unusual upright appearance. The lower leaves roll inward at the margins, becoming stiff and leathery. These leaves may eventually die prematurely and drop from the plant.

The plant essentially looks depressed and sickly from emergence through the entire growing season. This chronic infection pattern reflects virus accumulation that began in the seed tuber before planting.

Current Season Infection: From Aphid Vectors

Plants that become infected during the current growing season present different symptoms. Symptoms appear first on the youngest, uppermost leaves as the virus moves through the plant. Affected leaves develop an unusual upright orientation and chlorotic (yellow) appearance. The characteristic leaf rolling occurs as these upper leaves curl upward.

Late-season infections sometimes don't produce visible symptoms at all. The virus is present in the plant and transmitted to tubers, but external leaf symptoms may be subtle or absent, making detection difficult without laboratory testing.

Tuber Net Necrosis: The Hidden Damage

The most economically significant symptom appears in the potato tuber itself, not the leaves. Net necrosis appears as browning of the vascular tissue inside the tuber, creating a visible net pattern when the tuber is cut. This symptom only appears in susceptible varieties and only in tubers produced on infected plants.

Tubers with net necrosis are unsuitable for fresh market sales and seed stock. Processing companies reject them. Even potatoes that appear normal on the outside may have extensive vascular damage from net necrosis inside.

How PLRV Spreads: Understanding the Aphid Vector

Understanding how PLRV spreads is critical for management. The virus travels from plant to plant exclusively through aphid feeding, with the green peach aphid being the primary vector.

The Transmission Process

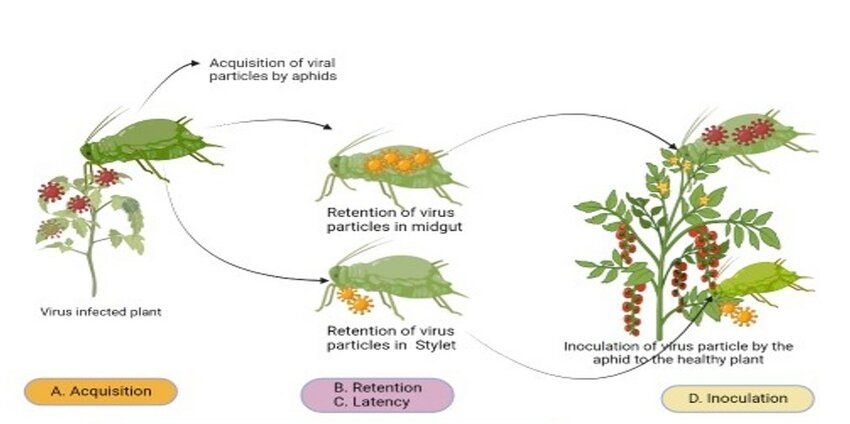

When an aphid feeds on a PLRV-infected plant, virus particles enter the aphid's digestive system. Unlike some viruses that replicate inside the vector, PLRV is a nonpropagative virus, meaning it doesn't multiply in the aphid. However, the virus circulates through the aphid's body and eventually reaches the salivary glands.

Once PLRV reaches the salivary glands, the aphid can transmit the virus to the next plant it feeds on. A single aphid bite lasting just minutes is sufficient for virus transmission after the acquisition period is complete. Several minutes to hours are required for the aphid to first acquire the virus, but once acquired, transmission can occur rapidly.

Spread Patterns

Winged aphids that migrate through the air can spread PLRV across long distances between fields. These migrants arriving from surrounding regions introduce virus into fields far from the original source. Within a field, wingless aphids crawling between adjacent plants ensure plant to plant spread continues throughout the season.

Early season aphid arrivals pose the greatest risk because any plants infected early in the season have months to accumulate virus and develop symptoms that attract more aphids.

Seed Tuber Transmission

PLRV-infected seed potatoes represent a massive risk. When infected seed tubers are planted, the virus is present throughout the emerging plant from day one. These chronically infected plants produce tubers destined for next season's seed supply that are already infected. This vertical transmission perpetuates the problem year after year unless interrupted by using certified, virus free seed.

Early Detection: Catching PLRV Before It Spreads

Early detection changes everything. A few infected plants caught in early July is manageable. The same problem discovered in August is devastating because the virus has had months to spread.

Visual scouting is your first line of defense. Walk your fields starting in early July, looking specifically for plants with rolled, waxy leaves, yellow coloration, and stunted growth. Note the location of affected plants. Scattered individual plants scattered throughout the field suggest current season aphid transmission. Large patches of affected plants suggest these areas were planted with infected seed.

When Do Symptoms Appear

Early infections that occur in June or early July produce visible leaf symptoms within three to four weeks of infection. Late-season infections might never show obvious symptoms, even though the virus is present and damaging tubers underground.

Laboratory Testing

For definitive diagnosis, laboratory testing confirms PLRV presence. ELISA (Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay) testing is the standard in most certification and testing programs. ELISA can detect PLRV at very low concentrations and provides rapid results, typically within 24 to 48 hours.

RT-PCR testing is more sensitive than ELISA and is considered the gold standard for virus detection, though it's more expensive and less commonly used for routine field screening.

Digital Diagnosis Tools

For those who want to document symptoms and get rapid identification help, AI-powered plant diagnostic tools like Plantlyze dot com allow you to photograph affected plants and receive identification suggestions. Their platform helps you track which fields show symptoms and when, building a disease history that informs future management decisions.

Prevention: Your Most Important Defense

Prevention is infinitely superior to treatment. Once PLRV infects your crop, damage is done. The virus doesn't go away, and management is expensive and incomplete.

Using Certified Seed Potatoes

Using certified virus free seed potatoes is your single most important management tool. Certified seed is tested and documented to be free of PLRV and other major viruses. This simple practice eliminates the most significant source of virus inoculum.

Seed certification programs operate under strict standards. Certified seed has been field inspected multiple times during the growing season and tested for virus presence. Foundation seed undergoes even more rigorous testing than certified seed.

The cost of certified seed is higher than uncertified seed, but the risk of crop loss from PLRV far exceeds the seed cost premium. A single year of PLRV-infected plantings produces infected seed that perpetuates the problem indefinitely.

Field Isolation

Potato fields should be isolated from each other by at least 200 yards when possible. This distance slows aphid flight between fields and reduces secondary spread. Some seed potato production areas maintain even greater distances between fields.

Removing volunteer potatoes from previous crops and controlling wild potato plants eliminates inoculum sources. These alternate hosts harbor PLRV throughout the season and serve as stepping stones for aphid vectors moving between fields.

Managing the Aphid Vector

Controlling aphids can slow PLRV spread, though controlling aphids alone doesn't guarantee PLRV prevention. Intense aphid populations combined with high virus inoculum pressure can overwhelm even aggressive insecticide programs.

Timing of Treatments

Early-season aphid control is essential. Insecticide applications in June and July can prevent or reduce primary infections from winged migrants. Once secondary spread is underway between plants in August and later, controlling all aphids becomes nearly impossible.

Seed treatment and in-furrow insecticides like neonicotinoid products provide early season protection. These systemic insecticides are taken up by the plant and incorporated into all tissues, providing residual protection throughout the critical early season period.

Foliar Insecticide Applications

Foliar insecticide sprays supplement seed treatments. Timing applications based on aphid monitoring with yellow sticky traps provides efficient, targeted control. Oil-based products and insecticidal soaps provide softer alternatives with shorter residual periods but better environmental profiles.

Resistance in Vectors

Repeated use of the same insecticide class leads to resistance development in aphid populations. Alternating between different chemical classes and modes of action slows resistance development. Neonicotinoids should be rotated with pyrethroids, organophosphates, and other chemistry to maintain effectiveness.

Resistant Varieties: A Management Tool

While no potato variety offers complete immunity to PLRV, some varieties tolerate the virus better than others, and many don't develop tuber net necrosis when infected.

Knowing which varieties develop net necrosis versus which tolerate infection without tuber damage guides variety selection for high-risk areas. Consulting your state's seed certification program or university extension service identifies varieties recommended for your region.

Molecular breeding advances continue improving PLRV resistance genetics. Researchers have identified QTL (quantitative trait loci) regions that confer PLRV resistance. Future varieties will likely incorporate stronger resistance genetics.

Integrated Management: Combining Multiple Tactics

The most effective PLRV management combines cultural, vector control, and varietal strategies. Single-tactic approaches fail eventually.

The Complete Strategy

Start with certified seed and field isolation. Rotate to new field locations, maintaining distance from previous potato plantings. Scout fields weekly beginning in June, looking for early symptom development. Remove any infected plants immediately. Monitor aphid populations with sticky traps and make insecticide applications based on population levels, not on a fixed schedule.

Select varieties that don't develop tuber net necrosis and that tolerate virus presence without severe yield loss. Maintain good records of virus presence, vector populations, and management timing. These records reveal patterns that inform future decisions.

Control weeds that serve as alternate hosts and seed fields from the healthiest, most vigorous plants. After harvest, clean equipment thoroughly before moving between fields.

This comprehensive approach dramatically reduces PLRV incidence and severity. No single tactic controls it completely, but the combination provides effective management.

Post-Harvest Considerations

After harvest, management continues. Infected tubers should be handled separately from clean seed stock. Storage conditions don't eliminate the virus, so proper tuber selection at harvest matters.

Select seed only from the healthiest plants in clean areas of the field. Store seed tubers at 45 to 50 degrees Fahrenheit with adequate air circulation to slow respiration and prevent secondary disease development.

Plantlyze dot com tools can help track which fields and blocks showed virus symptoms, allowing you to note areas to avoid when selecting seed tubers for next season's planting.

Moving Forward: Your Path to PLRV Control

Potato leafroll virus is manageable with proper prevention and early detection. The virus won't disappear, but its impact can be minimized through integrated management.

Start now by committing to certified seed for all plantings. Scout your fields regularly for symptom development. Control your aphid populations strategically. Select appropriate varieties for your growing region. Keep detailed records of virus occurrence and management responses.

The combination of these strategies, implemented consistently season after season, transforms PLRV from a serious threat into a manageable challenge.

References

1. UC Davis Integrated Pest Management Program

https://ipm.ucanr.edu/

2. University of Minnesota Extension

https://www.extension.umn.edu/

3. University of Idaho Extension Services

https://www.uidaho.edu/extension

4. Colorado State University College of Agricultural Sciences

https://www.colostate.edu/

5. Northwest Potato Research Consortium

https://www.nwpotatoresearch.com/

6. University of Florida Department of Entomology and Nematology

https://entnemdept.ufl.edu/