Every season, gardeners and farmers watch their potato crops with growing anxiety. One week, plants look healthy and vigorous. The next week, mysterious brown spots appear on leaves, spreading with alarming speed. Within days, an entire field can collapse into a rotting mass. This is potato late blight, and it remains one of the most destructive diseases threatening potato production worldwide.

If you have grown potatoes, you understand the frustration of late blight. This fungal disease can devastate crops seemingly overnight, turning your harvest into compost. The good news is that late blight is manageable when you understand what causes it, how to recognize it early, and which prevention and treatment strategies work best. This comprehensive guide covers everything you need to know to protect your potato crop.

What Is Potato Late Blight?

Potato late blight is a serious disease caused by the pathogen Phytophthora infestans. Despite its name suggesting a fungus, this organism is actually an oomycete, which scientists call a "water mold." This distinction matters because it affects how the disease spreads and which treatments work most effectively. The oomycete life cycle depends heavily on moisture, making environmental conditions critical to disease management.

Late blight has a dramatic historical significance. Between 1845 and 1852, this disease triggered the Irish Potato Famine, killing approximately one million people and forcing another million to emigrate. Understanding that such devastation came from a single pathogen underscores why modern farmers take late blight seriously.

Today, late blight remains the most economically damaging disease affecting potatoes globally. Crop losses can exceed 75 percent in regions with suitable conditions for disease development. The disease threatens production in cool, wet climates worldwide, from Europe and North America to Africa and Asia. Modern agriculture relies on prevention strategies and resistant varieties to keep late blight in check, but the threat persists whenever conditions favor disease spread.

Identifying Potato Late Blight

Recognizing late blight symptoms early is critical for managing the disease effectively. The sooner you identify infection, the more options you have to prevent it from spreading through your entire crop.

Early Symptoms on Leaves

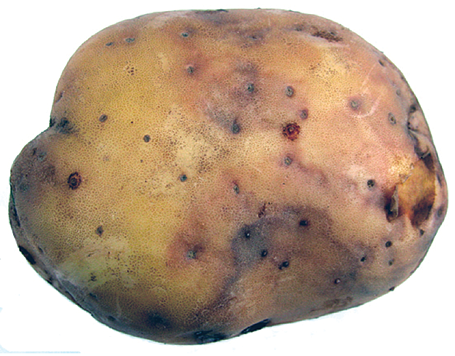

Late blight symptoms on potato leaves are distinctive once you know what to look for. Initially, small water-soaked spots appear, often with a grayish brown color. These lesions typically have a yellow or pale ring surrounding them, which helps distinguish late blight from other potato diseases.

In humid conditions, you will notice a white fuzzy growth on the undersides of affected leaves. This white growth consists of fungal structures called sporangia, which release spores that spread the disease. The appearance of this white fuzz indicates active disease transmission is occurring.

As the infection progresses, affected leaves wilt and collapse rapidly. The tissue turns brown and papery, eventually drying completely. Unlike some diseases that progress slowly, late blight can destroy a healthy leaf within 3 to 7 days under favorable conditions.

You might also notice a distinctive musty or fresh cut potato smell around infected plants, particularly in wet conditions. This characteristic odor comes from the tissue breakdown and fungal activity.

Stem and Tuber Symptoms

Late blight does not limit itself to leaves. Dark, water soaked lesions appear on potato stems and can extend into the tubers below the soil surface. When you dig infected plants, you will see brown discoloration in the upper portions of tubers, though the rot rarely extends deep into the tuber.

In storage, late blight can develop in two forms. Dry rot appears as hard, corky tissue with a wrinkled surface. Wet rot, more common in high moisture conditions, appears as a soft, mushy decay that spreads rapidly and develops a distinctive foul smell. Both forms render tubers unmarketable and unsuitable for seed.

Distinguishing Late Blight from Other Potato Diseases

Late blight often gets confused with early blight, another common potato disease. Understanding the differences prevents wasted management efforts.

Early blight typically appears first on lower, older leaves and shows concentric ring patterns (target spot) with a yellow halo. Early blight progresses slowly, taking 2 to 3 weeks to kill a leaf. Late blight appears simultaneously on leaves at all heights on the plant, lacks the distinct ring pattern, and kills leaves much more rapidly.

Early blight rarely produces the white fuzzy growth on leaf undersides that characterizes late blight. If you see that distinctive white fuzz, you have late blight. If you observe lesions with target ring patterns on lower leaves and slower disease progression, you likely have early blight.

When in doubt about disease identification, tools like Plantlyze can help. Plantlyze's AI powered plant care and diagnosis tool can analyze photos of affected plants and confirm whether you are dealing with late blight or another condition, helping you choose the right management strategy quickly.

How Late Blight Spreads

Understanding the disease cycle of late blight helps you anticipate when risk is highest and when prevention is most critical.

The Disease Cycle

Late blight spreads through two distinct reproductive phases. The asexual phase produces sporangia (specialized spore structures) that spread the disease locally and regionally. These sporangia release zoospores, which swim through water films on leaves to establish new infections. This asexual reproduction drives rapid disease spread during the growing season and is your primary management concern.

In cooler conditions, particularly in fall and winter, the pathogen produces oospores (resting spores) through sexual reproduction. These thick walled spores can survive in soil and in infected seed potatoes for months or even years. Oospores cause late blight outbreaks the following season when conditions become favorable.

Environmental Conditions That Favor Spread

Late blight thrives in cool, wet conditions. The optimal temperature range for disease development is 60 to 75 degrees Fahrenheit. Temperatures below 50 degrees or above 80 degrees slow disease spread significantly. This is why late blight is most problematic in spring and fall, when temperatures stay in the favorable range and moisture is abundant.

Moisture is equally critical. The pathogen cannot complete its lifecycle or spread effectively without extended leaf wetness. Rain is the primary moisture source, but even dew provides enough moisture for sporulation and infection. In regions where springs are cool and wet, late blight is virtually certain unless prevented through resistant varieties or fungicide applications.

High humidity alone, without actual leaf wetness, does not favor late blight as much as you might expect. The key is water films on leaf surfaces where the organism can grow and produce spores. Extended periods of wet leaves (10 to 12 hours or more) dramatically increase infection risk.

Seasonal timing differs by region. In temperate climates with spring rains, late blight typically emerges in May or June as temperatures warm and moisture increases. In subtropical regions with monsoon rains, the disease appears in winter months when rainfall is heavy. Understanding your region's risk period helps you time preventive measures properly.

Common Spread Sources

Contaminated seed potatoes are the most significant source of late blight in most regions. Oospores can survive in tuber tissue in storage, then germinate when seed pieces are planted in warm, moist soil. Using certified disease free seed potatoes eliminates this major risk factor.

Infected volunteer potato plants from previous crops also harbor the pathogen. These plants grow from tubers left in the field after harvest and can produce spores that infect nearby crops. Removing all volunteer potatoes before planting reduces this risk.

Diseased tubers in compost piles or improperly managed crop residue can maintain the pathogen over winter. Proper hot composting (temperatures exceeding 140 degrees Fahrenheit for several weeks) kills the pathogen, but cool or passive composting does not.

Agricultural equipment moved from infected fields to healthy fields can transport sporangia. Cleaning equipment between fields, particularly during wet conditions when spores are actively being produced, prevents this source of spread.

Prevention Strategies

Prevention is far more effective and economical than trying to cure late blight once it has established. A comprehensive prevention approach combines resistant varieties, cultural practices, and monitoring.

Pre-Planting Practices

Your first defense begins before planting. Purchase only certified disease free seed potatoes from reputable suppliers. These potatoes are grown under careful conditions where late blight cannot establish. The cost premium for certified seed is negligible compared to crop loss from early season infection.

Store seed potatoes at cool temperatures (around 40 degrees Fahrenheit) in well ventilated conditions until planting. This slows any disease progression if oospores are present. Do not store seed with other crops where disease could spread.

Review your field history. If late blight was present in previous years, that field carries elevated risk due to oospores in soil. Consider rotating to a different field if possible, or be prepared for increased management efforts.

Select varieties with resistance to late blight. This is one of the single most effective management strategies available. Resistant varieties can reduce late blight loss from 75 percent to less than 20 percent, even without fungicide applications.

During Growing Season

Proper spacing and air circulation reduce humidity around plants, making conditions less favorable for the pathogen. Plant rows at adequate distance (typically 30 to 36 inches between rows) and thin plants within rows if necessary. Air moving through the canopy dries leaves faster, reducing leaf wetness duration.

Irrigation timing dramatically affects disease risk. Water in the early morning, allowing foliage to dry before evening. Never use overhead sprinklers that keep leaves wet for extended periods. Drip irrigation eliminates this risk altogether.

Mulching provides secondary benefits. By keeping soil splash off lower leaves, mulch reduces spore movement from soil to foliage. Mulching also moderates soil temperature and moisture.

Crop rotation is essential. Never plant potatoes in the same field more frequently than every 3 to 4 years. This interval allows oospores in soil to die without viable seed potatoes to infect.

Scout your fields regularly, at least weekly once plants are 6 inches tall. Check both upper and lower leaf surfaces. Early detection allows you to make management decisions before disease becomes established.

Resistant Varieties

Multiple late blight resistant potato varieties are now available. The level of resistance varies by variety and region. In Lithuania and Eastern Europe, late maturing varieties like Vilnia and Vokė show excellent resistance. Early maturing varieties remain highly susceptible to late blight in these regions.

For Central Africa, resistant varieties developed by the International Potato Center, including CIP clones, have shown consistent resistance under field conditions. In Bangladesh, recently released varieties BARI Alu 46 and BARI Alu 53 demonstrated high resistance and yields exceeding 30 tons per hectare.

Selecting appropriate resistant varieties for your region requires consultation with local extension services or your seed potato supplier. They can recommend varieties known to perform well in your climate and soil conditions.

Cultural Management

Wide row spacing (30 to 36 inches minimum) and tall, hilled rows promote air movement that dries foliage quickly after rain. Eliminate all volunteer potato plants that emerge before spring planting. These plants are likely infected and serve as inoculum sources for your new crop.

Sanitize cultivation equipment between fields. In wet conditions, spore laden soil on equipment can introduce the pathogen to clean fields. A simple rinse with water or a bleach solution takes only minutes but prevents potentially catastrophic disease transfer.

Remove potato foliage 2 to 3 weeks before harvest if late blight is present. This prevents spores from entering the soil and establishing oospores in the tuber zone. Destruction of foliage also reduces spore sources in storage areas.

Treatment and Management Options

Despite your best preventive efforts, late blight can still emerge under ideal disease conditions. Understanding treatment options helps you respond quickly and protect your crop.

Chemical Control (Fungicides)

Fungicides fall into two categories: protectants and systemic materials. Protectant fungicides create a barrier on leaf surfaces that prevents spore germination. These must be applied before infection occurs. Once the pathogen is inside the plant, protectants cannot stop disease development.

Systemic fungicides are absorbed into plant tissue and move through the plant. Some systemic materials have curative activity, meaning they can stop infection even after the spore has germinated. Systemics provide longer lasting protection, typically 7 to 10 days versus 3 to 5 days for protectants. The trade off is cost (systemics are more expensive) and potential for resistance development if used repeatedly.

Timing fungicide applications based on weather forecasts maximizes effectiveness. Most potato growers use disease forecast models that predict when conditions favor infection. When risk reaches a threshold, spraying becomes necessary. In the United States, many growers follow disease severity value (DSV) models. When accumulated DSVs exceed 18 since the last spray, fungicide applications are recommended.

Application schedules vary with disease pressure. In low risk conditions, spraying every 10 to 14 days is adequate. During high risk periods with frequent rain and cool temperatures, spraying every 7 to 10 days may be necessary. Resistance management requires rotating between different fungicide classes to prevent the pathogen from developing resistance.

Organic and Biological Options

Copper fungicides provide reasonable late blight control in organic production. Copper works as a protectant, meaning it must be applied before infection. The copper ions denature proteins in germinating spores, preventing infection establishment. Once infection occurs, copper has no effect.

Copper effectiveness diminishes as plants grow and new unprotected foliage expands. Applications must continue throughout the season as plants develop. Overuse of copper, however, can cause phytotoxicity (plant damage) and accumulate in soil to toxic levels. Use copper as part of a rotation strategy, not as the only control method.

Sulfur based treatments show promise when combined with copper. Research on other diseases demonstrates that sulfur additions to copper fungicides can improve disease control, particularly during high infection pressure periods. This combination approach may offer improved organic control.

Biological controls using Bacillus subtilis bacteria show promise in research settings but remain inconsistent in field conditions. These materials work best as preventive applications and offer limited curative activity.

Seaweed based products and compost tea are frequently promoted for late blight control. While these materials may improve overall plant health, evidence for direct late blight control remains limited.

Emergency Response If Infection Found

If you discover late blight in your field, immediate action is critical. Isolate the infected area if possible to prevent spread to adjacent plants. Mark affected plants clearly so your spraying crew can prioritize fungicide application to surrounding plants.

Destroy infected foliage and stems. Remove them from the field and either incinerate them or hot compost them (temperatures exceeding 140 degrees Fahrenheit for several weeks). Do not compost infected tissue in a cool pile where oospores will survive.

Tubers can sometimes be salvaged if only foliage is infected. Destroy all foliage 2 to 3 weeks before harvest to allow soil to dry around tubers. Avoid overhead irrigation. This timing prevents oospores from entering the soil and establishing in tuber zones.

In storage, maintain cool temperatures (around 40 degrees Fahrenheit), good air circulation, and remove any tubers showing rot symptoms. Monitor stored potatoes frequently, as late blight in tubers can spread rapidly in warm, moist storage conditions.

When late blight is widespread throughout the field, destroying the entire crop may be the only option to prevent disease spread to neighboring fields and future crops.

Decision Making Framework

Deciding whether to apply fungicides or simply let the crop go depends on several factors. Consider the market value of your potatoes, the cost of fungicide and application, the likelihood of disease developing, and the availability of resistant varieties for future seasons.

Seed potato production requires higher disease control standards than fresh market or processing potatoes. An infection in seed potatoes means that disease is dispersed to every field where those seeds are planted. Some seed potato producers use mandatory fungicide schedules regardless of disease pressure, as the risk of losing the seed certification is too great.

Tracking disease pressure through the season helps refine future management decisions. Keep records of when disease first appeared, which fungicides you used, how effective they were, and rainfall and temperature data. This history becomes invaluable for predicting disease pressure and planning management in future years.

Using Plantlyze for Early Detection

Early detection of late blight symptoms gives you the maximum response time to manage the disease. This is where diagnostic tools become valuable. Plantlyze's AI powered plant care and diagnosis system allows you to photograph suspicious plant symptoms and receive instant analysis identifying whether you are dealing with late blight or another condition.

By catching late blight in its earliest stages, you can make immediate management decisions. Removing a few infected plants from the edge of the field is far easier than treating the entire field once disease becomes widespread. Use Plantlyze's plant health check service at plantlyze.com to verify disease identification and get recommendations for your specific situation. Early intervention using this kind of digital tool can literally save your harvest.

Conclusion

Potato late blight remains a serious threat to potato production, but it is far from an inevitable disaster. By implementing a comprehensive approach combining resistant varieties, cultural practices, monitoring, and timely treatment decisions, you can successfully manage this disease.

Prevention is always your best strategy. Choose resistant varieties suited to your region, scout your fields regularly, maintain proper plant spacing and irrigation practices, and use disease forecast models to time management actions. These practices provide cost effective, sustainable late blight management that works year after year.

Monitor your plants closely, particularly during cool, wet periods when late blight risk is highest. The few minutes you spend scouting plants each week can reveal infections early, when your management options are greatest. Use tools like Plantlyze to confirm disease identification and receive expert guidance on next steps.

Finally, recognize that your region's late blight situation is shared with neighboring farms and gardeners. Practices like destroying volunteer plants, using certified seed, and preventing disease spread on equipment benefit everyone in your community. Coordinate with neighbors, share information about disease appearance timing and severity, and together work toward sustainable potato production in your region.

References

1. University of Wisconsin Vegetable Pathology

https://vegpath.plantpath.wisc.edu/diseases/potato-late-blight/

3. Royal Horticultural Society (RHS)

https://www.rhs.org.uk/disease/potato-blight

4. ATTRA/NCAT Organic Farming Resources

https://attra.ncat.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/lateblight.pdf

5. eOrganic Extension Network

https://eorganic.org/pages/18361/organic-management-of-late-blight-of-potato-and-tomato-phytophthora-infestans