Potato dry rot is the single most important cause of postharvest losses in potato storage facilities across the United States and worldwide. Unlike those diseases which are principally pre-harvest infections in the field, dry rot is basically a postharvest infection developing during storage where, if not properly checked by condition management, can silently wipe out an entire stockpile. Every year massive losses take place in commercial storage facilities and home gardening operations. The most baffling fact is that dry rot can totally be controlled by the proper method of curing and storage, which includes handling at harvest, hence all prevention measures are within your control. Understanding how this fungal disease develops and implementing comprehensive management strategies allows you to protect your potato investment and maintain valuable crop quality throughout the storage season.

What Is Potato Dry Rot?

Potato dry rot is a fungal disease by several species of Fusarium among which Fusarium sambucinum is the most important and aggressive pathogen in almost all regions. Other species that shall also be considered as pathogens are Fusarium solani and Fusarium oxysporum. The predominance of these species varies with geographic location and environmental conditions.The disease earned its name from the characteristic "dry" nature of the rot it produces, distinguishing it sharply from bacterial soft rot, which creates wet, slimy lesions that spread rapidly throughout tuber tissue.

The Fusarium fungi responsible for dry rot are ubiquitous in soil and present on the surface of virtually all potato tubers. But none of these pathogens just simply penetrate an intact and healthy potato skin. They require a wound or cut through which they can also infect the tuber. This is critical in understanding dry rot prevention, becoming infection during harvest, handling, and seed preparation because it means injury while harvesting, handling, and preparing seed directly influences the development of the disease.

The disease is unique among postharvest potato infections because it develops slowly but persistently during storage. Where bacterial soft rot can encompass an entire tuber within days, dry rot progresses gradually, creating internal cavities and tissue breakdown over weeks and months. This slow progression makes early detection and swift action crucial for limiting losses.

Recognizing Potato Dry Rot Symptoms: What to Look For

Learning to identify dry rot at different stages allows you to catch the disease early and prevent it from spreading through your stored potatoes. The symptoms vary depending on disease stage and storage conditions.

Initial and Developing Symptoms

Dry rot symptoms begin inconspicuously with small brown to black flecks appearing on the tuber surface, typically at wound sites such as bruises, cuts from seed cutting, or mechanical damage during harvest. These initial lesions develop where Fusarium spores have entered through broken skin. As the infection progresses, lesions enlarge gradually and deepen in color, ranging from light brown to dark brown or nearly black.

The characteristic sunken appearance develops as tissue inside the tuber deteriorates and collapses. This creates a visible depression on the tuber surface, often with a distinctly wrinkled texture surrounding the lesion. The wrinkled patches give dry rot a distinctive appearance that experienced storage managers learn to spot immediately.

Advanced Disease and Cavity Formation

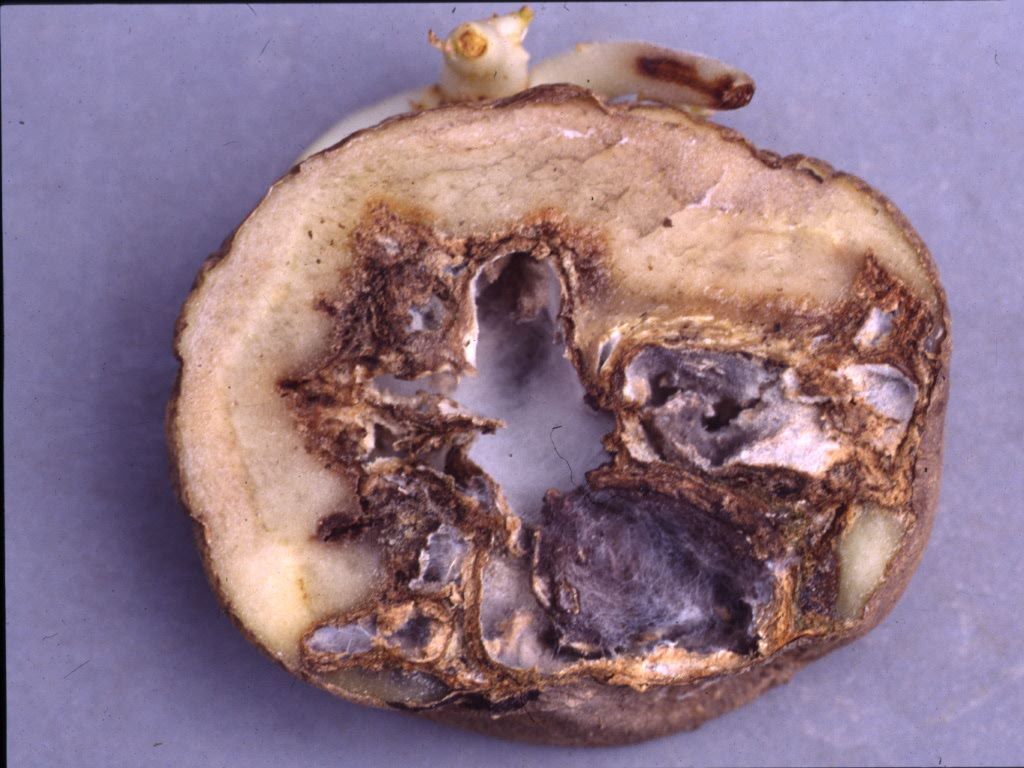

As dry rot progresses deeper into the tuber, it creates large hollow cavities and internal rot chambers. The internal tissue color changes to light to dark brown or black, depending on the Fusarium species and tuber condition. In some cases, the pathogen essentially rots out the center of the tuber, creating empty spaces surrounded by healthy-looking external tissue until the final stages.

White, pink, or yellow cottony mold may become visible on the tuber surface, particularly as the disease progresses and the tuber spends more time in storage. This fungal growth consists of mycelial mass and spore-producing structures that indicate active disease development. Pink or brick orange colored spore masses sometimes develop, depending on the Fusarium species and storage humidity conditions.

Complications with Secondary Infection

A complicating factor in storage occurs when soft rot bacteria invade tubers already infected with dry rot fungus. At this point, the progression becomes dramatically accelerated. A rapid wet decay is caused by bacterial soft rot which can encompass the whole tuber within days masking completely the initial symptoms of dry rot. This secondary infection becomes more of a problem if storage conditions are wet or humidity is above optimum levels.

When you encounter what appears to be soft rot, there's often dry rot underneath that initiated the infection. Proper diagnosis becomes important because the management strategies differ between predominantly fungal and predominantly bacterial disease.

Understanding Fusarium Species and Infection Mechanisms

Different Fusarium species dominate in different regions, and understanding which pathogen you're dealing with can influence management decisions.

Regional Variation in Species

Fusarium sambucinum is the most important dry rot pathogen in the northeastern United States and remains the most damaging species overall. However, Fusarium solani is also prevalent and causes significant losses. In Michigan and other regions, Fusarium oxysporum commonly causes dry rot alongside Fusarium sambucinum. Geographic surveys show Fusarium graminearum as the dominant dry rot agent in North Dakota, Tunisia, and Canada. This species variation matters because some fungicides work better against certain species than others.

How the Disease Infects Tubers

Fusarium infection requires a wound or rupture in the tuber skin, lenticels, or unhealed seed piece surfaces. The fungus cannot penetrate intact, suberized (healed) seed pieces. Once entry occurs through a wound, the infection hyphae grow within intercellular spaces of living plant cells. The fungus only becomes intracellular after the plant cell dies. This distinction is important because wound healing through suberization can prevent infection even after exposure to the pathogen.

Mycotoxin Production Concerns

Many Fusarium species produce mycotoxins as part of their disease mechanism, adding a food safety dimension to dry rot management. Fusarium sambucinum produces trichothecene mycotoxins including sambutoxin, zearalenone, and deoxynivalenol. These mycotoxins are toxic to plants and animals and can be present in infected potatoes. Susceptibility of potato cultivars to infection correlates highly with mycotoxin concentration in infected tubers.

While cooking at high temperatures reduces mycotoxin content significantly (26 percent reduction at 100 degrees Celsius for one hour, increasing to 100 percent reduction at 121 degrees Celsius for four hours), some residual toxins may remain in processed potato products. This food safety concern adds another reason to prevent dry rot infection and avoid storing heavily infected potatoes.

How Potato Dry Rot Develops: Understanding the Disease Cycle

Dry rot development follows a predictable pattern once wounds are present and storage conditions favor fungal growth.

Wound Creation During Harvest and Handling

The entire dry rot cycle begins with mechanical injury to tuber skin. Harvest equipment damages potatoes when machines dig tubers, bruising and cutting them during the extraction process from soil. Potatoes are bumped and bruised as they move through conveyor systems, graders, and sorting equipment. Transportation between field and storage can cause additional damage. If seed potatoes are cut for planting, those cut surfaces represent major infection sites.

Every wound is an opportunity for Fusarium spores to establish infection. This is why minimizing damage during harvest is absolutely critical for dry rot prevention.

Wound Healing and Suberization

The good news is that potato wounds heal themselves through a process called suberization, where the tuber forms a protective cork-like layer over the wound. This healing process takes time and requires proper conditions. Temperatures of 50 to 55 degrees Fahrenheit with good ventilation and high humidity (above 90 percent) promote rapid wound healing. Once a wound is fully suberized, Fusarium spores cannot penetrate, essentially immunizing that wound against infection.

The curing period immediately after harvest is when this critical healing occurs. If tubers are cooled too quickly or exposed to poor conditions before wounds heal, Fusarium can establish infection in the fresh wounds.

Development During Storage

Once wounds are healed and tubers are placed in storage, conditions determine whether dry rot develops or remains dormant. Cool storage temperatures slow fungal growth and disease progression significantly. But longer storage time at higher temperatures permits progressive development of rots. The critical factor is in the humidity because high moistures and condensation give growth to fungus.

If secondary soft rot bacteria attack the lesions of dry rot, then the disease attains full acceleration consuming sometimes the whole tuber within a few days. This is particularly problematic in wet storage conditions with poor ventilation.

Prevention Strategies: Building Comprehensive Dry Rot Management

Dry rot prevention requires multiple integrated strategies working throughout the harvest, storage, and monitoring cycle. No single practice prevents dry rot alone. Instead, combining several approaches creates layers of protection.

Starting with Clean, Certified Seed

Your first line of defense begins with seed selection. Use clean seed with minimal dry rot from reputable suppliers. Request seed health certification documentation confirming that seed stock has been inspected for disease. Inspect all seed tubers before planting, looking for any visible signs of rot, soft spots, or surface lesions.

This simple step eliminates dry rot problems from the outset because you're not planting fungal spores into the field.

Seed Treatment and Equipment Disinfection

If you cut seed potatoes, several management practices reduce disease transmission. Treat cut seed with effective fungicides including fludioxonil, flutolanil, or mancozeb, which have proven efficacy against Fusarium species. Sharpen cutting knives regularly for clean cuts that heal faster than ragged cuts. Disinfect cutting equipment thoroughly between seed lots and periodically during cutting to prevent pathogen transmission from infected to healthy tubers.

Avoid holding pre-cut seed in conditions lacking adequate airflow, as this creates humid, wet environments favoring fungal growth. Allow cut surfaces to dry completely before planting.

Optimal Planting Conditions

Create conditions that favor rapid wound healing by warming seed tubers to 50 degrees Fahrenheit before cutting and maintaining soil temperatures of at least 45 degrees Fahrenheit at planting. Keep soil moisture between 60 to 80 percent of field capacity to avoid waterlogged conditions. Plant seed pieces warmer than the soil temperature they're being planted into, which promotes suberization. Avoid irrigation before plant emergence, as it creates conditions favoring infection.

These specific conditions reduce seed piece decay significantly by promoting rapid wound healing.

Harvest Timing and Technique

Harvest only after tubers have reached proper skin maturity, which typically occurs 3 or more weeks after vine death. This ensures tuber skin has thickened and wounds heal more readily. Minimize wounding and bruising during harvest by ensuring equipment is properly adjusted. Harvest in cool conditions when possible, maintaining tuber pulp temperatures between 50 to 64 degrees Fahrenheit to slow fungal growth.

Every wound prevented during harvest is one less infection site for Fusarium spores to colonize.

Curing Period Management

The 2 to 3 weeks immediately following harvest is the critical curing period when wounds heal. During this time, maintain tuber temperature around 50 to 55 degrees Fahrenheit with good air circulation and relative humidity above 90 percent. Do not drop storage temperature immediately after harvest because rapid cooling prevents proper wound healing and allows Fusarium to establish infection.

The goal during curing is allowing the tuber to form protective periderm over all wounds while minimizing weight loss and disease development.

Storage Facility Management

Cleanliness and disinfection establish the foundation for healthy storage. Thoroughly clean all dirt and debris from storage facilities, as organic matter reduces disinfectant effectiveness. Steam wash surfaces and use approved disinfectants with adequate contact time (at least 10 minutes) to kill pathogens.[52] Ensure continuous air circulation throughout storage with functioning ventilation systems.

Store potatoes in shallow piles rather than deep bins to improve air circulation and eliminate hot spots where disease concentrates. Maintain relative humidity between 90 to 95 percent to prevent excessive dehydration while controlling condensation. Temperature must remain stable and cold, avoiding exposure of cool potatoes to warmer outside air, which causes condensation and promotes bacterial soft rot.

Storage Monitoring and Intervention

Scout storage regularly for signs of dry rot including sunken areas, wrinkled patches, discolored tubers, and mold growth. Use infrared thermometers to detect hot spots in the pile that indicate disease activity or ventilation problems. Document the location and extent of any rot found.

When dry rot is discovered, market potatoes with significant disease development as quickly as possible rather than leaving them in storage. Never return graded tubers to storage after removing them, as this practice spreads disease throughout the pile. Segregate potatoes from high-risk harvest areas into separate sections or trucks for immediate processing.

Fungicide Treatments

ost-harvest fungicide treatments can provide additional protection when disease risk is high. Stadium (azoxystrobin, fludioxonil, and difenoconazole) applied to clean tubers has been shown to significantly reduce Fusarium dry rot during storage. Ensure good coverage by rolling the tubers through the spray application. The timing of application and fungicide selection should be made in consultation with extension services or fungicide product labels.

Fungicide resistance has developed in some Fusarium populations, particularly to thiabendazole (TBZ), making active ingredient rotation important for maintaining treatment efficacy. Vary the fungicide modes of action used to prevent resistance development.

When Dry Rot Appears: Management During Storage

Despite best prevention efforts, dry rot sometimes develops during storage. Knowing how to respond minimizes losses and prevents spread.

Recognition and Documentation

Monitor stored potatoes throughout the season, particularly during the first month of storage when disease symptoms become visible. Look for the characteristic sunken, wrinkled lesions that indicate dry rot. Note the exact location and extent of infection. Early detection prevents extensive spread through the storage pile.

Fungicide Options for Developing Disease

If dry rot is detected early, post-harvest fungicide application may limit further disease spread. Stadium application on tubers showing early rot symptoms can prevent disease progression, though efficacy decreases as infection becomes established. Consult extension advisors on fungicide timing and application when disease is identified.

Swift Marketing of Affected Potatoes

The most practical response to significant dry rot development is rapid removal and marketing of affected potatoes. Do not attempt to store potatoes with extensive dry rot damage, as disease will progress. Plan for quick movement to processing facilities or markets where tubers can be processed immediately. Storing diseased potatoes risks spreading infection to nearby healthy tubers.

Modern Diagnosis and Emerging Detection Technologies

Traditional identification of dry rot relies on visual symptom observation, but modern diagnostic tools offer faster, more accurate confirmation.

Laboratory and Molecular Methods

Conventional diagnostics include fungal isolation and identification through culturing and microscopic examination. PCR (polymerase chain reaction) and molecular detection methods enable rapid species identification. Real-time PCR provides quantitative determination of pathogen load in tubers or soil. PCR-ELISA assays combine molecular specificity with quantitative measurement capabilities. DNA sequencing definitively confirms Fusarium species, which can influence fungicide selection.

Emerging Technology Approaches

Thermography based detection systems use infrared imaging to spot temperature differences which indicate activity of the disease inside thereby spotting early dry rot in storage. Machine learning systems, trained on thousands of images, can easily identify and classify severities and progression patterns of dry rot.[54][59] Assessment over a large potato pile without destructive sampling is made possible by these approaches.

AI powered plant diagnosis systems represent the cutting edge of disease identification. Plantlyze and similar platforms enable growers to photograph suspicious tubers and receive instant identification of potential diseases. These systems, trained on extensive disease image libraries, can identify dry rot and other storage diseases rapidly in the storage facility environment. Access to tools like Plantlyze at plantlyze.com allows quick confirmation of suspected dry rot when standard laboratory testing would delay management decisions.

Distinguishing Dry Rot from Other Storage Diseases

Proper disease identification ensures you implement appropriate management responses.

Dry Rot versus Soft Rot

Bacterial soft rot causes wet, slimy decay that rapidly encompasses entire tubers, sometimes within days. Soft rot produces clear fluid discharge when tubers are squeezed. Dry rot, by contrast, causes slow, non-slimy decay with internal cavity formation. When soft rot bacteria colonize dry rot lesions, the combined infection accelerates dramatically, creating confusion in diagnosis.

Other Storage Diseases

Pink rot (Phytophthora) causes wet lesions and discoloration distinct from dry rot. Leak (Pythium) creates a clear fluid exudate when squeezed. Late blight causes less aggressive rot that generally doesn't penetrate the tuber center. Blackheart (physiological disorder from low oxygen) causes smoky gray to black discoloration, but tissue remains firm and is never brown.

Accurate identification determines whether management should focus on fungal control versus bacterial management or physiological improvements.

Future Directions: Emerging Management Approaches

Beyond conventional fungicides and cultural practices, research is developing innovative dry rot management strategies.

Biocontrol organisms including Bacillus subtilis and Pseudomonas fluorescens show promise for reducing dry rot infection in greenhouse and storage trials. Carboxylic acid treatments are being evaluated as alternative management approaches. Combination strategies pairing biocontrol organisms with conventional fungicides may offer superior control.

Non-thermal technologies like high pressure processing can reduce mycotoxin content in infected potatoes, making affected product safer for consumption. HPP treatments can inactivate fungal spores and reduce mycotoxin concentrations significantly, though implementation is still emerging in commercial potato operations.

Genetic resistance development continues as breeders identify and incorporate resistance traits into commercial potato varieties. Growing disease-resistant varieties offers promise for reducing infection risk at the source. However, no potato variety is completely resistant, making combined management approaches still essential.

Your Comprehensive Dry Rot Management Plan

Implementing effective dry rot prevention requires commitment to multiple practices applied consistently from harvest through storage. Start with the fundamentals: source clean, certified seed and minimize damage during harvest. Implement a rigorous curing period that allows wound healing while preventing disease. Manage storage conditions obsessively, controlling temperature, humidity, and ventilation to prevent fungal growth.

Scout your storage regularly, watching for the sunken, wrinkled lesions that indicate dry rot development. Use diagnostic tools like Plantlyze at plantlyze.com for rapid symptom confirmation when you suspect disease. Remove diseased potatoes immediately rather than attempting long term storage. Plan for quick marketing of potatoes with disease history.

Rotate fungicide active ingredients if you use chemical treatments, preventing resistance development. Train your staff to identify dry rot symptoms early and respond swiftly. Combine cultural practices with fungicide treatments and emerging technologies for the most complete protection.

Dry rot need not devastate your potato crop. Commercial growers protecting crops and operations worldwide demonstrate that comprehensive, integrated dry rot management allows successful potato production year after year. With understanding of how this disease develops and consistent implementation of the proven management strategies outlined in this guide, you can protect your potato investment and maintain healthy, valuable stored potatoes throughout the season regardless of initial infection risk.

References

Cornell Vegetables (Cornell University) — https://www.vegetables.cornell.edu/pest-management/disease-factsheets/fusarium-dry-rot-of-potato/

UC IPM (University of California) — https://ipm.ucanr.edu/agriculture/potato/fusarium-dry-rot-and-seed-piece-decay/

Michigan State University — https://www.canr.msu.edu/resources/potato_diseases_fusarium_dry_rot_e2992

NIH/PMC (National Institutes of Health) — https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7609731/

APS Journals (American Phytopathological Society - Peer-Reviewed) — https://apsjournals.apsnet.org/doi/10.1094/PHP-07-25-0178-PDMR