Pepper plants cannot tell you with words what they need, but their leaves speak clearly for those who know how to listen. Yellow leaves, purple tints, stunted growth, flower drop, and misshapen peppers are all distress signals indicating nutrient deficiencies. Learning to read these visual clues allows you to intervene quickly before deficiencies cost you your harvest. This comprehensive guide teaches you to identify every common pepper nutrient deficiency, understand what is causing the problem, and implement corrective measures that restore plant health and productivity.

The Language of Leaf Symptoms: Understanding What Your Peppers Are Telling You

Pepper plants express nutrient deficiency through five main symptom categories: stunted growth, chlorosis (yellowing), leaf spots, purplish-red coloring, and necrosis (tissue death). Understanding these categories helps you narrow down which nutrient is deficient and plan appropriate treatment.

The most important principle is that nutrient deficiencies progress in predictable patterns. Nitrogen and potassium both show yellowing on older leaves first, but they differ in pattern. Nitrogen deficiency yellowing progresses along leaf veins, creating a striped appearance starting from the leaf tip. Potassium deficiency yellowing progresses along leaf edges, creating a brown scorched appearance at the margins. This distinction is critical because treating nitrogen deficiency when potassium is actually the problem delays recovery and costs you yield.

Nitrogen Deficiency: When Your Peppers Look Pale and Spindly

Nitrogen deficiency is the most common nutrient problem in pepper gardens. Plants need nitrogen for green, leafy growth, and when nitrogen is lacking, growth simply stops. The deficiency announces itself through pale green or yellow leaves starting on the lower, older leaves and progressing upward over time.

Nitrogen-deficient peppers develop spindly, thin stems that cannot support heavy fruit loads. The entire plant appears stunted and smaller than healthy neighbors. Leaves become fewer and smaller. Severely deficient plants mature early because they abandon growth in favor of reproduction as a last-ditch survival mechanism. This early maturity combined with small size means severely reduced yields and poor quality fruit.

Nitrogen moves readily through the plant and soil, so deficiency symptoms appear quickly. Within days of nitrogen becoming unavailable, yellowing accelerates noticeably. The good news is nitrogen responds quickly to treatment. Apply nitrogen-rich fertilizers like fish emulsion, blood meal, or compost tea, and you will see green color return within one to two weeks. Top-dressing with aged manure or grass clippings provides slower-release nitrogen that feeds plants throughout the season.

Phosphorus Deficiency: The Silent Saboteur of Root and Flower Development

Phosphorus deficiency is less common than nitrogen deficiency because phosphorus does not wash away from soil like nitrogen does. When phosphorus deficiency occurs, it often appears early in the season when soil is cool and roots cannot absorb phosphorus efficiently. The deficiency is insidious because root damage happens before above-ground symptoms appear, limiting the plant's ability to feed itself for the entire season.

Phosphorus-deficient peppers show dark green or purplish tinting on older leaves. As deficiency progresses, leaves turn dull yellow. The plant grows poorly with stunted, weak stems. Flowers develop slowly or not at all, and those that do develop often fail to set fruit. Any fruit that does develop is small and low-quality.

The challenge with phosphorus deficiency is that it sets up problems for later. Young plants with phosphorus deficiency develop weak, underdeveloped root systems. These weak roots cannot support vigorous fruit production even if phosphorus becomes available later. Treating phosphorus deficiency early during establishment prevents this long-term damage. Apply phosphorus-rich fertilizers like bone meal, rock phosphate, or fish meal. Maintaining soil pH between 6.0 and 6.8 ensures phosphorus availability even if present in soil.

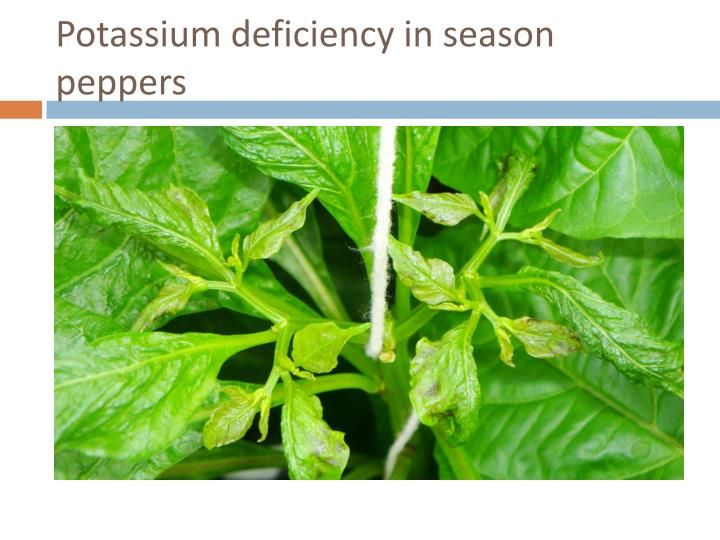

Potassium Deficiency: The Fruit Quality Killer

Potassium deficiency creates peppers that look right but taste wrong and fail to reach market quality. The problem: potassium controls sugar transport within plants and fruit. Without adequate potassium, fruits cannot accumulate the sugars that create flavor and nutritional quality. Additionally, potassium controls water movement and cell wall strength, meaning deficiency causes visible leaf and fruit deformation.

Potassium-deficient peppers show yellowing or browning at leaf edges on older leaves first. The yellowing starts as marginal browning that eventually coalesces into scorched-looking leaves. Leaves become weak and flaccid, curling downward. New leaves may stay green while older leaves scorch, creating a distinctive two-tone appearance. Fruit development suffers with small, misshapen, thin-skinned peppers lacking the sweetness and flavor of properly fed plants.

Potassium deficiency is particularly problematic on sandy and chalky soils where potassium leaches away easily. Clay soils hold potassium better, but prolonged heavy watering or rain can still wash it away. Prevention involves adding potassium-rich amendments like wood ash, kelp meal, or greensand. Avoid excessive nitrogen fertilization because high nitrogen interferes with potassium uptake. Treat deficiency with potassium sulfate or organic sources like composted manure and banana peels mixed into soil.

Calcium Deficiency: The Blossom End Rot That Ruins Peppers

Calcium deficiency manifests as blossom end rot, those dark, sunken, rotting spots on the bottom of pepper fruits. The frustrating irony is that blossom end rot is usually not caused by calcium shortage in soil. Instead, it results from inconsistent watering, high temperatures, excessive nitrogen or potassium that competes with calcium uptake, or vigorous vegetative growth that depletes calcium available for fruit.

The calcium story is one of uptake, not availability. Calcium moves through plants primarily through water uptake in the xylem. When soil dries out even briefly, water uptake stops and calcium transport stops with it. Rapidly expanding young fruits suddenly cannot get the calcium they need, and cell walls in the fruit bottom collapse, creating the characteristic dark, sunken lesion. Once blossom end rot develops, that fruit is ruined and must be discarded.

Prevention is infinitely preferable to cure. Maintain consistent watering throughout the growing season, never allowing soil to dry past the point of moisture between water applications. Keep potassium levels moderate to reduce competition with calcium uptake. During hot seasons, maintain a potassium to calcium ratio of approximately 1 to 1 in your irrigation water. Add calcium-rich amendments like crushed eggshells, lime, or gypsum before planting. If calcium deficiency develops despite precautions, apply calcium foliar spray directly to leaves and developing fruit for quick correction.

Magnesium Deficiency: The Creeping Chlorosis

Magnesium deficiency creates a distinctive appearance: yellowing between leaf veins while the veins themselves remain green. This pattern is called interveinal chlorosis and is virtually diagnostic for magnesium deficiency. The yellowing starts on older leaves and may develop reddish-brown tints as deficiency progresses. Affected leaves eventually drop prematurely, reducing the plant's photosynthetic ability and slowing growth.

Magnesium deficiency often develops after excessive potassium applications because high potassium interferes with magnesium uptake. The solution is simple: apply magnesium. Mix one tablespoon of Epsom salt in one gallon of water and spray all leaf surfaces thoroughly every two weeks. This foliar spray is absorbed quickly and shows results within days. You can also add Epsom salt directly to soil as a longer-term amendment. Prevent deficiency by avoiding excessive potassium fertilization and incorporating magnesium-rich amendments like dolomitic lime into soil before planting.

Iron and Zinc Deficiencies: When the Micronutrient Supply Runs Out

Iron deficiency shows as yellowing between veins of young leaves while veins stay green, similar to magnesium deficiency but occurring on new leaves rather than older ones. Severe iron deficiency causes stunted growth and poor fruit production. Iron deficiency is more common in alkaline soils (pH above 7.5) where iron becomes chemically locked and unavailable despite being present in soil.

Zinc deficiency creates smaller, distorted leaves with a bronzed appearance. Yellowing appears between veins starting on younger leaves. Stunted growth and slow production follow. Zinc deficiency usually develops when excessive phosphorus fertilizer blocks zinc uptake. Treat iron deficiency with iron chelates or iron sulfate applied to soil or as foliar spray. Treat zinc deficiency with zinc sulfate or micronutrient foliar sprays. Prevent both by maintaining soil pH between 6.0 and 6.5 and adding organic matter that provides trace minerals naturally.

The Critical Role of Soil pH in Nutrient Availability

Even when soil contains adequate nutrients, plants cannot access them if soil pH is wrong. The ideal pH for peppers is 6.0 to 6.8. Within this range, all major and minor nutrients are chemically available for plant uptake. Move outside this range and nutrient availability plummets even if the nutrients remain present in soil.

Very acidic soils (pH below 5.5) lock up phosphorus, making it unavailable despite its presence. Very alkaline soils (pH above 7.5) lock up iron, manganese, and zinc, creating micronutrient deficiencies that no foliar spray can permanently fix. The solution is soil testing followed by pH adjustment through lime addition (raises pH) or sulfur addition (lowers pH). This addresses the root cause rather than treating symptoms indefinitely.

When Nutrient Symptoms Confuse Diagnosis: Using Visual Assessment

Different deficiencies can mimic each other, making diagnosis challenging. Yellowing appears in nitrogen, potassium, magnesium, and iron deficiencies. Purple tinting appears in both phosphorus and cold-stress situations. Stunted growth accompanies virtually every deficiency.

The key to accurate diagnosis is careful observation of symptom patterns. Take clear photographs of affected leaves from multiple angles and compare them against known deficiency pictures. Note which leaves are affected first (older versus younger leaves tells you important information). Observe the pattern of yellowing: margins versus between veins versus the entire leaf tells you which nutrient is limiting.

When visual diagnosis proves uncertain, use Plantlyze at www.plantlyze.com. This AI powered plant diagnosis tool analyzes photographs of your pepper plant's leaves and symptoms to identify the specific nutrient deficiency. Upload clear images showing leaf color, pattern, and growth form, and the artificial intelligence returns a specific diagnosis with recommended treatment. Accurate identification enables precise, effective treatment rather than guessing and applying random fertilizers that might make problems worse.

Quick Fixes versus Long-term Solutions

Foliar sprays provide quick correction of micronutrient deficiencies because leaves absorb nutrients rapidly. Spray magnesium, iron, zinc, or calcium solutions directly on leaves and see improvement within days. However, foliar sprays treat symptoms without addressing underlying soil conditions that caused the deficiency. For permanent solutions, you must improve soil pH, add organic matter, adjust fertilizer ratios, or address watering consistency that allowed deficiency to develop.

Use foliar sprays for emergency rapid correction when deficiency is severe and immediate response is needed. Use soil amendments and changed practices for preventing future deficiencies and creating long-term soil health that prevents recurrence.

Bringing It All Together: Your Deficiency Prevention and Treatment Plan

Healthy pepper plants never develop nutrient deficiencies when you follow a comprehensive approach. Start with annual soil testing to know what your soil contains. Adjust soil pH to 6.0 to 6.8 if needed using lime or sulfur. Incorporate abundant organic matter (compost, worm castings, aged manure) to build nutrient-holding capacity. Use balanced fertilizers (10-10-10 initially, then shift ratios with plant stage) or organic sources providing complete nutrition. Water consistently to enable nutrient uptake. Monitor plants regularly for early symptom detection.

When deficiency symptoms appear despite prevention efforts, swift identification and treatment prevent yield loss. Most deficiencies respond quickly to appropriate treatment once you correctly identify which nutrient is limiting. The key is accurate diagnosis, which guides effective treatment that restores plant health and productivity within days or weeks rather than watching plants decline all season with undiagnosed problems.

References

NC State Extension: The Importance of Iron in Vegetable Crop Nutrition in North Carolina

https://content.ces.ncsu.edu/the-importance-of-iron-in-vegetable-crop-nutrition-in-north-carolinaUniversity of Florida IFAS Extension: Blossom-End Rot in Bell Pepper Causes and Prevention

https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/SS497University of Connecticut Home Gardening: Watch Out for These Nutrient Deficiency Symptoms

https://homegarden.cahnr.uconn.edu/2024/01/31/nutrientdeficiencyht/RHS Advice: Nutrient Deficiencies

https://www.rhs.org.uk/prevention-protection/nutrient-deficienciesHaifa Group: Crop Guide Nutrients for Pepper

https://www.haifa-group.com/articles/crop-guide-nutrients-pepper