Introduction: When Your Cucumbers Look Sick But Aren't Diseased

Your cucumber leaves are yellowing despite adequate watering. You search for disease or pest damage but find nothing. The plants just look unhealthy and unproductive. Frustration sets in. What is actually wrong?

Nutrient deficiency is often the invisible culprit. Unlike obvious disease or pest damage, nutrient problems develop gradually and subtly. Many home gardeners mistake deficiency symptoms for disease, applying fungicides that do not help. In reality, their plants simply need better nutrition.

The good news is identifying and correcting nutrient deficiencies is straightforward once you understand what to look for. This guide teaches you to read the visual language your plants use to communicate their nutritional needs, then correct problems quickly.

Why Nutrient Deficiency Matters in Cucumbers

Cucumbers are vigorous growers with substantial nutritional demands. Producing abundant fruit while maintaining healthy vines requires continuous nutrient supply throughout the growing season. Unlike slower-growing plants, cucumbers cannot tolerate even brief nutritional shortages without visible consequences.

The symptoms of nutrient deficiency often get misidentified as disease. A gardener sees yellowing leaves and assumes powdery mildew or disease. They spray fungicide that solves nothing because the real problem is inadequate nitrogen. This misdiagnosis wastes time, money, and effort while plants continue declining.

Early identification of nutritional problems proves crucial because corrections work quickly once you supply the missing nutrient. Nitrogen deficiency responds within three to seven days of correction. Other deficiencies take longer but typically resolve within two to three weeks. Waiting until deficiency becomes severe wastes precious growing season.

Untreated nutrient deficiencies dramatically reduce yields and fruit quality. Poor-quality fruit does not develop properly, lacking firmness, color, and commercial appeal. Plants produce less fruit total as nutritional stress shifts energy toward survival rather than reproduction.

How to Read Nutrient Deficiency Symptoms

Nutrient deficiency symptoms follow patterns you can learn to recognize instantly. Understanding these patterns separates frustrated gardeners from successful ones.

The location of symptoms matters tremendously. These elements, nitrogen, potassium, magnesium and phosphorus are mobile (transported to other parts of the plant), due to which, when their supplies become low, plants move these out from the older leaves in case of a deficiency. Immobile nutrients (calcium, iron, manganese, zinc, boron and copper) exhibit symptoms on the newest growth because they cannot be moved from old tissues to new sites of growth.

Color patterns reveal specific deficiencies. Uniform yellow foliage suggests different problems than interveinal yellowing (yellow between veins with green veins remaining). Leaf margin scorching (brown edges) indicates different deficiencies than overall paleness.

Symptom progression tells you severity and helps differentiate from disease. Nutrient deficiency develops gradually, affecting entire plant areas uniformly. Disease typically shows spotting patterns or concentrated areas rather than uniform symptoms across the plant.

Nitrogen Deficiency: The Most Common Problem

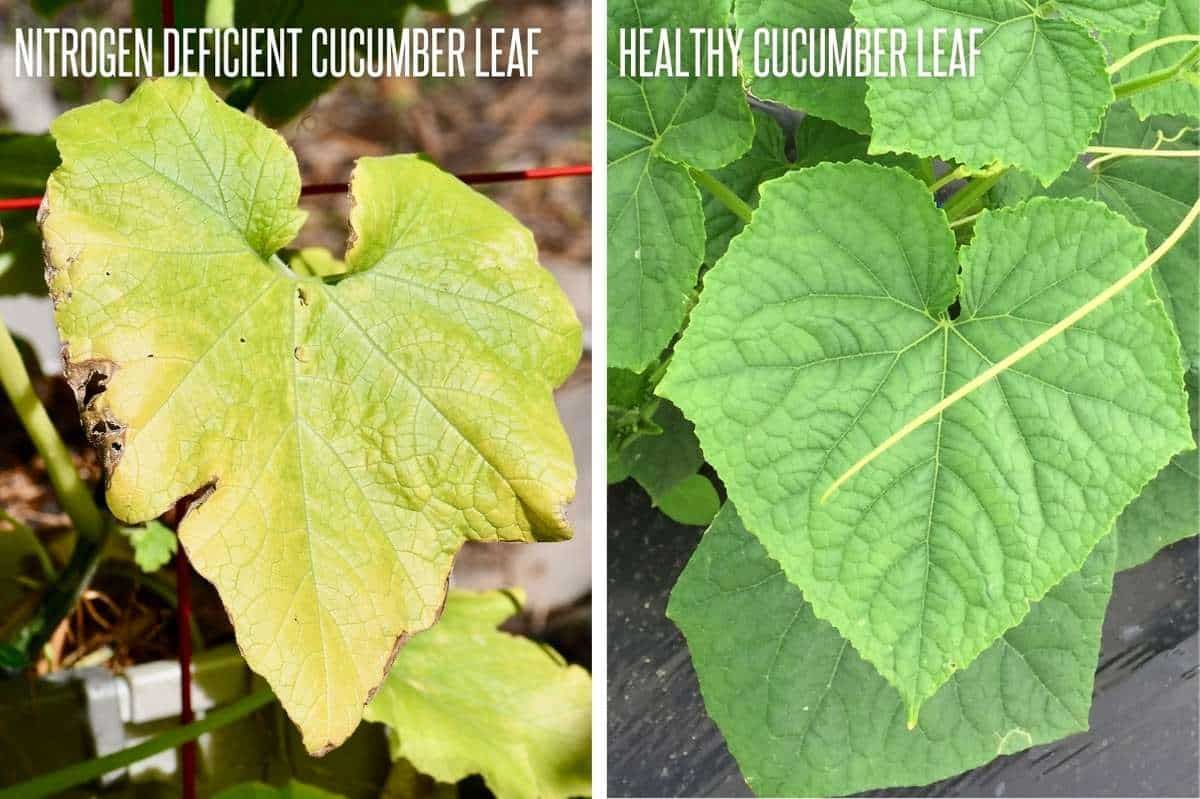

Nitrogen deficiency is by far the most common nutrient problem home gardeners encounter with cucumbers. It is also the easiest to recognize and correct quickly.

Nitrogen deficiency begins on the oldest leaves, creating uniform yellowing that moves progressively upward through the plant as deficiency worsens. The yellowing is pale and widespread rather than spotted or concentrated. Affected leaves eventually become almost completely yellow while new growth remains green initially.

The entire plant appears weak and stunted. Vines grow slowly. Leaf size decreases. The plant loses vigor and never reaches full productive potential. Fruit production drops significantly because the plant lacks energy for extensive fruiting.

Nitrogen is highly mobile in plants, moving from old leaves to new growth when supplies are inadequate. This explains why older leaves yellow first while new foliage temporarily stays green. As deficiency worsens, new growth eventually yellows as well.

Several factors cause nitrogen deficiency. Nitrogen is also leached quickly by water from light, sandy soils. The soil’s nitrogen supply does not meet heavy cropping demands. Sometimes, excessive levels of potassium or phosphorus interfere with NBPT nitrogen absorption, causing functional deficiency even when there is enough soil-supplied N. Soils with high pH may limit the availability of nitrogen.

The solution is simple: inject some nitrogen. Side-dress around plants with balanced fertilizer, use foliar spray for quick response, or inject liquid fertilizer to irrigation systems. Visible improvement from nitrogen applications occurs in three to seven days, so this is one of the more rewarding changes you can make.

For cucumbers grown in containers, nitrogen application rates of around 150 to 200 ppm (parts per million) are advised. Cucumbers grown in the field usually require 100 to 150 pounds of N per acre, depending on soil type.

Potassium Deficiency: The Fruit Quality Thief

Potassium deficiency is insidious because it does not obviously stunt plant growth like nitrogen deficiency. Instead, it quietly sabotages fruit quality while the plant appears deceptively healthy.

Potassium deficiency first appears as marginal chlorosis, a yellowing or browning of leaf edges while the interior remains green. As deficiency progresses, these leaf margins become scorched and necrotic (dead tissue). Older leaves show these symptoms first, eventually developing upward-curled leaf edges that look crinkled or cupped.

The devastating consequence appears in the fruit. Potassium-deficient cucumbers develop poor shape, uneven coloration, reduced firmness, and decreased shelf life. Commercially, such fruit becomes unmarketable. Home gardeners notice their cucumbers lack the satisfying crunch and firmness of properly nourished plants.

Potassium mobility in soil is much slower than nitrogen, making potassium problems more challenging to correct quickly. Potassium-rich soils often develop potassium availability issues due to interactions with calcium and magnesium. Sandy soils commonly show potassium deficiency because potassium leaches easily and does not bind tightly to sandy particles.

Heavy fruit production demands are particularly vulnerable to potassium deficiency. Potassium concentrates in fruit, so heavily fruiting plants deplete soil potassium rapidly.

It takes some time for potassium deficiency to be corrected; much longer than in the case of nitrogen. Foliar application is more rapid than soil treatment and improvement can be seen in 7 to 10 days. Soil potassium accumulates more slowly, requiring weeks to correct.

Recommend potassium levels for containers cucumbers are 160 to 200 ppm; in the field, 100-200 pounds of potash per acre is required, based on soil test levels.

Magnesium Deficiency: The Hidden Problem

Magnesium deficiency frequently goes unrecognized because gardeners expect symptoms to look like nitrogen deficiency. Instead, magnesium deficiency shows a distinctive and beautiful pattern gardeners sometimes miss entirely.

Magnesium deficiency appears as interveinal chlorosis specifically on older leaves. The major veins remain green while the tissue between veins becomes yellow. This creates a striped or net-like appearance that is quite distinctive once you know what to look for.

In severe cases, affected leaves develop tan or reddish-brown burn between the veins. Leaf edges may curl upward and become brittle. Leaves sometimes develop a purple-red tint in extreme deficiency before dying and dropping from the plant.

Magnesium is mobile in plants, moving from old to new tissue when supplies dwindle. This explains why older leaves show symptoms first. But interactions with other nutrients make magnesium deficiency particularly maddening.

Sometimes an 'overabundance' of nitrogen, potassium, or calcium can stop the magnesium from being absorbed - causing a deficiency despite there being adequate amounts in the soil. This adversarial relationship means that one nutrient imbalance is sometimes remedied only by losing ground in others.

It is extremely easy and cheap to correct the magnesium deficiency. Epsom salt, magnesium sulfate, supplies immediate magnesium. Dissolve 1 tablespoon of Epsom salt per gallon of water and use as a foliar spray. Do this weekly until all your symptoms vanish, but usually only three or four applications are required.

Or, sprinkle one to two tbsp of Epsom salt around the base of each plant and water in well, then repeat weekly as necessary. Recovery is seen in seven to ten days usually.

Phosphorus Deficiency: The Overlooked Issue

Phosphorus deficiency is less common than nitrogen or potassium problems but devastating when it occurs. The distinctive symptoms help identify it once you know what to look for.

Phosphorus deficiency causes older leaves to develop red or purple discoloration. This reddish tint affects the entire leaf initially, later concentrating on leaf edges and veins. The plant may appear dark green overall despite obvious nutrient stress.

Phosphorus-deficient plants show severely stunted growth. New leaf development slows dramatically. Flowering and fruit production decline markedly. Roots fail to develop properly, creating weak, vulnerable plants.

Unlike mobile nutrients, phosphorus is immobile in plants. Once it concentrates in plant tissues, it cannot be redirected to new growth. This explains why phosphorus deficiency causes overall stunting rather than specific leaf yellowing.

Phosphorus availability depends heavily on soil pH. Cold soil temperatures reduce phosphorus availability even in well-amended soils. High pH or low pH soils often show phosphorus deficiency because phosphorus becomes locked up in forms plants cannot absorb.

Phosphorus deficiency correction is slow. Unlike nitrogen which shows response within days, phosphorus takes ten to fourteen days to produce visible improvement. This delay occurs because phosphorus corrects slowly in plant systems.

Recommended phosphorus rates are approximately 50 to 100 ppm for container cucumbers. A soil test provides specific recommendations based on your soil conditions.

Calcium Deficiency: The Blossom-End Problem

Calcium deficiency shows distinctive symptoms that home gardeners often attribute to disease or environmental stress rather than nutrition.

New leaves develop twisted, distorted, or scorched appearances. Leaf curling downward becomes pronounced. Growth abnormalities appear almost immediately as new foliage emerges looking permanently damaged.

The most dramatic symptom appears on fruit as blossom-end rot. Dark sunken spots develop on the fruit bottom (blossom end), creating unmarketable, rotted fruit. This distinctive symptom is so recognizable that many gardeners immediately know calcium is involved.

Calcium is immobile in plants, explaining why new growth shows symptoms first. Calcium problems relate less to available soil calcium than to calcium uptake problems caused by inconsistent watering or poor drainage.

Blossom-end rot occurs as a lack of calcium predominantly in the new fruit. During fruit swelling, erratic watering checks the supply of calcium to the developing fruit. The farthest end of the fruit from the stem (blossom end) is most distant from the nutrient supply and therefore, most susceptible to calcium deficiency.

Water management, rather than calcium application is the key to the solution. Calcium problems are best avoided with a regular supply of water, mulch to moderate fluctuation in moisture and good drainage rather than supplementing soil with extra calcium.

If calcium application becomes necessary, apply gypsum or agricultural lime according to soil test recommendations. However, prevent the problem through care rather than trying to correct it with supplements.

Other Important Micronutrients

Beyond the major nutrients, cucumbers require several micronutrients in smaller quantities. Deficiencies of these elements create distinctive symptoms worth recognizing.

Iron deficiency appears as interveinal yellowing specifically on new leaves. The veins remain green while tissue between veins becomes pale yellow, creating a net-like pattern. This symptom concentrates on newest growth, moving downward as deficiency worsens. Iron deficiency typically occurs in high-pH soils where iron becomes chemically unavailable despite being present in soil. Apply chelated iron foliar spray according to product directions, or acidify soil slightly to increase iron availability.

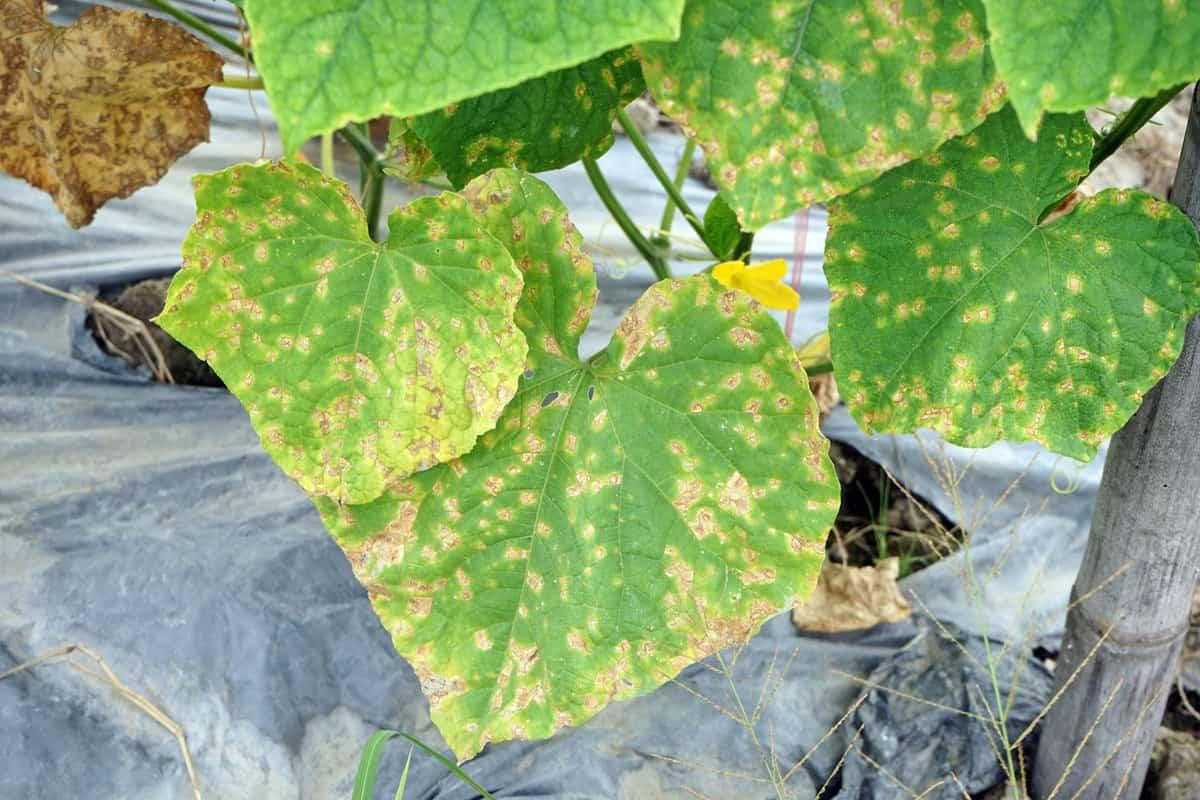

Manganese deficiency creates small reddish-brown spots on older leaves combined with yellowing between veins. The leaf tissue becomes gray or brown spotted rather than uniformly colored. This deficiency occurs in neutral to high-pH soils. Apply manganese sulfate foliar spray or soil drench according to product directions.

Zinc deficiency causes new leaves to become pale green with a mottled appearance. Pinhead-sized spots appear on leaves. Plant stunting becomes pronounced. Zinc deficiency is particularly common in high-pH or compacted soils. Apply zinc sulfate according to product label rates.

Boron deficiency creates twisted, distorted new leaves that fail to develop normally. Stems may become hollow and brittle. Boron deficiency is less common than other micronutrient problems but causes severe growth abnormalities when it occurs. Apply borax or boric acid according to label directions very carefully as boron toxicity is possible with over-application.

Copper deficiency produces twisted new leaves similar to boron deficiency combined with yellowing leaf edges on older foliage. Copper deficiency is rare in most soils but common in peat-based growing media. Apply copper sulfate according to label directions if deficiency is confirmed.

Sulfur deficiency creates uniform yellowing across all foliage without the green veins remaining that characterize iron deficiency. The entire plant appears dull yellow. Sulfur deficiency is uncommon in soils but possible in peat-based systems. Apply sulfate salts or elemental sulfur depending on specific deficiency type and pH requirements.

Identifying Multiple Deficiencies

Challenging growing conditions may result in several nutrient deficiencies at the same time. Understanding and addressing this type of situation requires a systematic approach.

Common pairings are N and K deficiencies. Fruit forming in large quantities, both nutrients are depleted simultaneously, especially in sandy soils subject to leaching. Another frequent combination links magnesium and potassium deficiency when high nitrogen application inhibits the availability of both.

Element interactions complicate diagnosis. High potassium depresses magnesium and calcium absorption. High nitrogen reduces potassium uptake. Alkaline pH reduces micronutrient availability. These competing relationships also mean that fixing one issue sometimes means tweaking others.

Soil testing is the best way out of multiple deficiencies. A full soil test reveals current nutrient levels, which means that you can target the fix without just guessing. Costs are often low at many university extension offices for soil testing.

If there is a suspicion of more than one deficiency being present, use a balanced complete fertilizer containing all the majors rather than single-element products. Follow with micronutrient spray if you notice any micronutrient symptoms.

Addressing Nutrient Deficiency: Solutions

Soil Testing: The Foundation

Soil testing provides baseline data for all nutrition decisions. A proper soil test reveals nutrient levels, pH, organic matter content, and texture information that guides all corrective actions.

University extension offices offer soil testing services at reasonable cost, typically 20 to 50 dollars per sample. This single test prevents guessing and wasted money on unnecessary amendments. Test before planting for best results, though mid-season testing helps troubleshoot existing problems.

Correcting Deficiencies Quickly

Foliar spray provides the fastest nutrient response. Nutrients applied directly to leaves absorb within hours through the leaf surface. This method works particularly well for quick nitrogen correction or micronutrient applications.

Mix fertilizer at half the recommended rate for foliar application to avoid leaf burn. Apply early morning or late evening when temperatures are cool and leaves remain moist longer. Spray until complete leaf coverage including undersides. Repeat applications every seven to ten days until symptoms disappear.

Soil application through side-dressing or irrigation works slower than foliar spray but provides sustained correction. Apply fertilizer in a band around plants, water thoroughly, and repeat on schedule. Liquid fertilizer injection through irrigation provides consistent delivery without burn risk.

Long-Term Prevention

Preventing deficiency proves simpler than correcting it. Establish a consistent feeding program appropriate for your growing conditions.

Use balanced fertilizer with roughly equal proportions of nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium. Apply every two weeks at recommended rates (approximately 150 to 200 ppm nitrogen for container cucumbers). Adjust rates based on plant appearance, increasing feeding if plants look pale or decrease if leaves become unusually dark.

Include micronutrients in your program through a complete fertilizer containing all essential elements. This preventive approach costs little but prevents frustration from unexpected deficiencies.

Maintain soil pH between 6.0 and 6.8 for optimal nutrient availability. Outside this range, nutrients become locked in soil forms plants cannot access. Annual compost incorporation builds organic matter that buffers pH and improves nutrient-holding capacity.

Prevention: Creating Optimal Nutrition

Begin with a soil test determining your starting nutrient levels. Based on results, amend soil with appropriate fertilizers before planting.

Use high-quality potting mix or garden soil amended generously with compost. Compost provides slow-release nutrients while building soil structure and microbial activity that supports plant nutrition.

Apply consistent balanced fertilizer throughout the growing season. For greenhouse or container cucumbers, maintain electrical conductivity (EC) between 2.0 and 2.5 mhos, which indicates adequate nutrient concentration.

Mulch heavily with organic material to regulate moisture and maintain consistent nutrient availability. Mulch gradually breaks down to build soil organic matter, creating long-term fertility improvement.

Water consistently to maintain even soil moisture. Inconsistent watering disrupts nutrient uptake and creates artificial deficiencies despite adequate soil nutrients.

Manage pH appropriately for your specific situation. Most cucumbers prefer slightly acidic conditions around 6.5 pH. If your soil pH drifts, apply lime to raise pH or sulfur to lower pH as needed.

Monitor plants weekly for early symptom appearance. Early intervention prevents problems from becoming severe. Photographic documentation helps track nutrient status across the season.

Common Nutrient Problem Misdiagnosis

Many gardeners misidentify nutrient problems as disease, applying inappropriate treatments that waste effort.

Nitrogen deficiency causes uniform yellowing that resembles powdery mildew's white coating at first glance. Closer inspection reveals complete absence of white powder and progressive yellowing of entire leaves rather than powdery mildew's distinctive white spots. Checking for disease presence prevents applying fungicide to a nutrition problem.

Potassium deficiency leaf edge scorching resembles herbicide damage. Herbicide damage typically concentrates on one side of the plant or follows spraying patterns, while nutrient deficiency distributes uniformly. Visual pattern recognition differentiates these problems.

Magnesium interveinal yellowing resembles iron deficiency. Both show green veins with yellow between them, but magnesium deficiency appears on older leaves while iron deficiency concentrates on new growth. Checking leaf age clarifies the distinction.

Water stress creates yellowing and wilting that mimics various deficiencies. Checking soil moisture and ensuring consistent watering prevents misdiagnosis. Plants recovering from drought often show false nutrient symptoms that resolve once watering normalizes.

For uncertain diagnoses, tools like Plantlyze dot com allow you to upload plant photos for AI-powered analysis. This helps confirm whether you are facing nutrient deficiency, disease, pest damage, or environmental stress.

Nutrient Excess: When More Is Not Better

Excessive fertilization creates problems as serious as deficiency. Understanding nutrient excess prevents these self-inflicted problems.

Nitrogen excess causes soft, weak plant growth prone to disease. Excessive vegetative growth produces few flowers and fruits. Leaves become huge but weak. Plants collapse easily under weight or wind stress. Reduce nitrogen feeding if plants show overly dark foliage and excessive vegetative vigor without proportional fruit production.

Potassium excess interferes with magnesium and calcium uptake, creating secondary deficiencies despite adequate amounts of these nutrients in soil. This antagonistic relationship means correcting one problem sometimes creates another.

Salinity from excess fertilizer burns root systems and reduces water uptake. Leaves develop brown tips and margins despite adequate water. In container growing, this problem accumulates rapidly as dissolved salts concentrate without drainage options. Flush soil thoroughly with water to reduce salt concentration if excess fertilization occurs.

Signs of over-fertilization include excessively dark foliage, poor flower production despite vigorous growth, brown leaf tips, and reduced plant response to watering. Reduce fertilization rate and increase water volume to flush excess salts if over-fertilization is suspected.

Seasonal Nutrition Adjustments

Nutrient needs change as plants progress through growth stages. Adjusting fertilization programs accordingly optimizes results.

Early season emphasis leans toward nitrogen to support vigorous vine development. Fruit production is not yet critical, so nitrogen drives vegetative growth. Apply balanced or nitrogen-emphasized fertilizer during establishment phase.

As flowering begins, shift toward potassium-emphasized fertilizer. Potassium supports fruit development, flavor, and shelf life. Increase potassium relative to nitrogen once fruiting begins.

During peak fruit production, maintain consistent potassium feeding. Potassium-rich fertilizer supports continued fruit production while nitrogen remains adequate but not excessive.

Late season adjustments depend on desired outcomes. For extended harvest, maintain feeding through season end. For end-of-season crop, reduce nitrogen feeding to prevent stimulating excessive new growth before the season closes.

Conclusion: Nutrient Problems Have Simple Solutions

Nutrient deficiency identification and correction is straightforward once you understand what to look for. Visual symptoms tell you exactly what your plants need if you learn to read the language plants use.

Prevention through consistent feeding programs prevents most nutrient problems before they develop. Soil testing provides certainty about your starting point. Regular monitoring catches problems early when correction is most effective.

Correction is often remarkably simple. Nitrogen deficiency responds within days to feeding. Magnesium deficiency corrects with inexpensive Epsom salt treatment. Most problems resolve within two to three weeks of appropriate correction.

This season, implement soil testing, establish a consistent feeding program, and monitor plants weekly for early symptom appearance. Address problems immediately when they emerge. By season end, you will notice dramatically healthier plants, improved fruit production, and better fruit quality resulting from optimized nutrition.

For photo-based disease and deficiency confirmation when symptoms are unclear, use Plantlyze dot com. Upload images of affected leaves and receive AI-powered analysis suggesting likely causes and appropriate solutions for your specific situation.

References

1. Haifa Group (Crop Nutrition Research)

https://www.haifa-group.com/cucumber-0/crop-guide-nutrients-cucumber

2. Auburn University Extension

https://www.aces.edu/blog/topics/crop-production/greenhouse-cucumber-production/

3. PMC NCBI (National Center for Biotechnology Information)

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11609769/

4. Royal Horticultural Society

https://www.rhs.org.uk/prevention-protection/nutrient-deficiencies

5. University of Hawaii Department of Agriculture

https://www.ctahr.hawaii.edu/oc/freepubs/pdf/RES-151.pdf

6. e-GRO (Greenhouse Management Research)

https://www.e-gro.org/pdf/E404.pdf

7. University of Alaska Fairbanks Extension

https://www.uaf.edu/ces/publications/database/gardening/growing-cucumbers-greenhouses.php

8. Oklahoma State University Extension

https://extension.okstate.edu/fact-sheets/cucumber-production.html

9. e-GRO Potassium Deficiency Guide

https://www.e-gro.org/pdf/E613.pdf

10. University of Georgia AESL (Fertilizer Recommendations)

https://aesl.ces.uga.edu/publications/soil/cropsheets.pdf

11. Nature (Scientific Journal - Deficiency Diagnosis Research)

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-025-97585-0

12. NSW Department of Primary Industries (Australia)

https://www.dpi.nsw.gov.au/agriculture/horticulture/greenhouse/pests,-diseases-and-disorders/cucumber-nutrition