Introduction

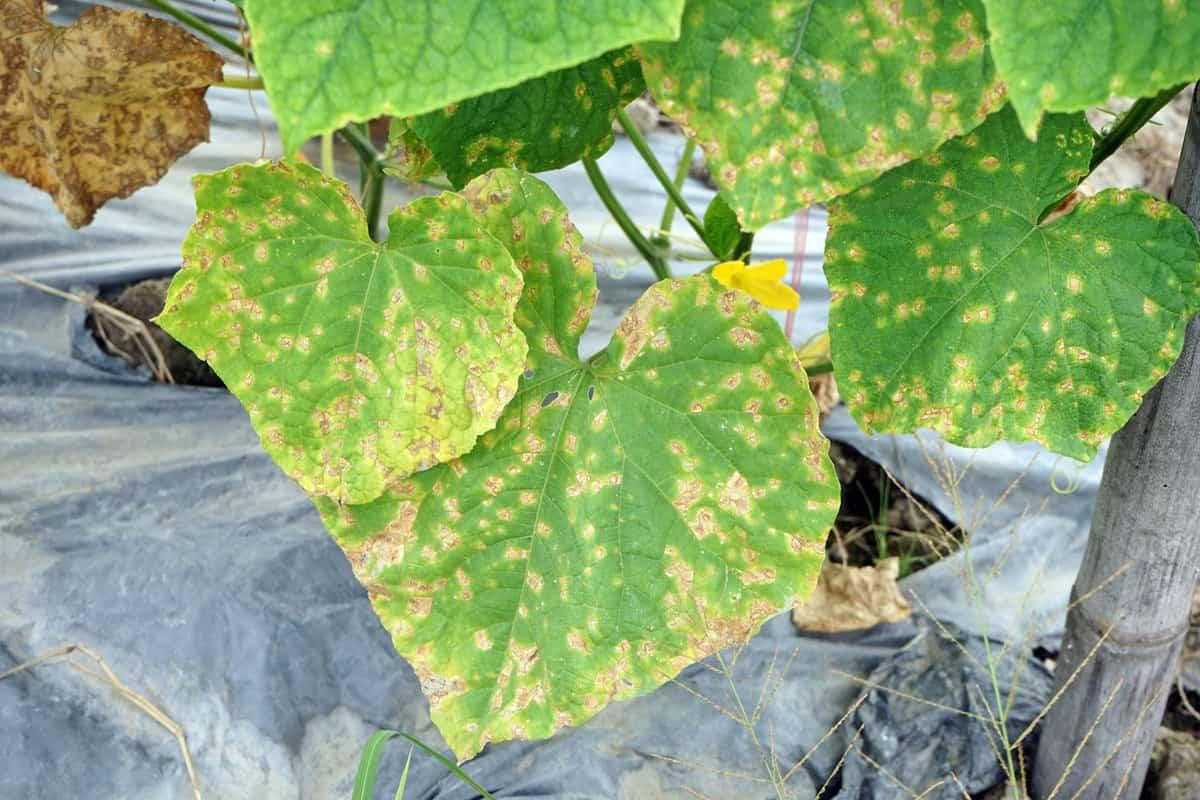

Picture discovering beautiful cucumber plants that suddenly develop strange mosaic patterns across their leaves. The leaves show mottled colors, twist unnaturally, and the plants stop growing. Within days, the fruit becomes deformed and unmarketable. This nightmare scenario represents cucumber mosaic virus (CMV), one of the most economically destructive plant viruses affecting global agriculture.

Cucumber mosaic virus threatens production across the world, affecting not just cucumbers but also melons, squash, peppers, legumes, and over 300 plant species total. The virus spreads exclusively through aphid vectors that are nearly impossible to eliminate completely. What makes CMV particularly devastating is that no chemical cure exists once plants become infected. Prevention becomes your only viable defense strategy.

Profitable production, rather than total crop loss, can be the result of an understanding of CMV transmission and recognition of its early symptoms together with knowledge about some preventive measures. This profitable guide walks you through everything you need to know about identifying, preventing, and managing cucumber mosaic virus. From certified seed selection to aphid vector control, you'll learn how to protect your cucumber crops and maintain consistent, disease-free production across multiple seasons.

What is Cucumber Mosaic Virus and Why It Matters

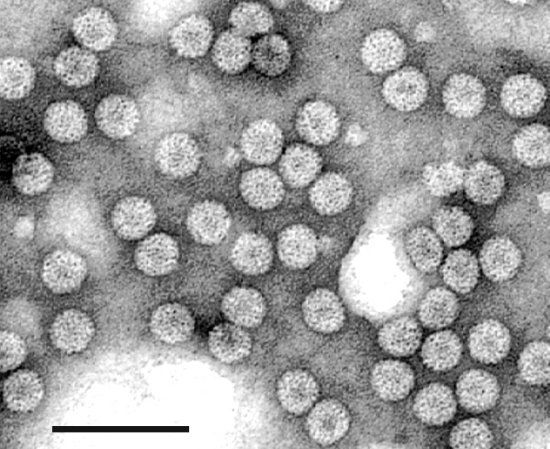

Cucumber mosaic virus belongs to the genus Cucumovirus and ranks among the most economically important plant viruses globally. The virus affects an extraordinarily broad host range, infecting over 300 plant species including vegetables, fruits, legumes, ornamentals, and weeds. This expansive host range explains why CMV emerges as such a persistent production challenge.

The virus exists as a positive-sense, single-stranded RNA pathogen that replicates within plant cell cytoplasm. Once inside a host plant, the virus uses the plant's cellular machinery to produce thousands of copies of itself. These viral particles spread systematically throughout the plant, infecting nearly every cell and causing the characteristic mosaic symptoms.

What makes CMV uniquely challenging is that no chemical treatment can cure an infected plant. Antibiotics do not work because viruses are not bacteria. Fungicides do not work because viruses are not fungi. Once a plant becomes infected, the only option is removal. This reality makes prevention absolutely essential for economic viability.

The global economic impact of CMV cannot be overstated. Losses in susceptible crop production exceed hundreds of millions of dollars annually. The virus causes yield reductions, fruit quality losses, and complete unmarketability of affected produce. In severe epidemics, growers lose entire harvests and must replant fields after disease pressure subsides.

How CMV Spreads: Understanding Transmission Mechanisms

Cucumber mosaic virus spreads through multiple routes, but aphids represent the primary vector in field production. Understanding these transmission pathways helps you implement targeted prevention strategies.

Aphids as the Primary Vector

Aphids transmit CMV in a non-persistent manner, meaning the virus does not replicate within the aphid body. Instead, the virus attaches to the aphid's mouthpart stylet (the tube-like feeding appendage). When an aphid feeds on an infected plant, the virus adheres to the stylet. The aphid can then transmit the virus to a healthy plant with its very next feeding, even if only for seconds.

Multiple aphid species efficiently transmit CMV. Aphis gossypii (cotton aphid), Myzus persicae (green peach aphid), and Aphis glycines (soybean aphid) all serve as vectors. This diversity of vectors makes aphid control extremely challenging because multiple species from different geographic regions can transmit the disease.

Infected plants modify their own characteristics to actually attract more aphids. The CMV virus manipulates plant physiology to make infected plants more appealing to aphids, creating a self-amplifying transmission mechanism. This viral strategy ensures greater spread to additional plants, perpetuating the infection cycle.

Other Transmission Routes

Seed transmission occurs in some crop species, though the rate remains variable. Cucumber seed transmission rates are generally low, but some crops experience higher transmission through seed. Using certified virus-free seed becomes important because even low transmission rates can introduce CMV into previously disease-free fields.

Mechanical transmission through human contact is theoretically possible but occurs rarely in commercial production. Gardeners who handle multiple plants can inadvertently spread CMV through contact if they do not wash hands or disinfect tools between plants.

Identifying Cucumber Mosaic Virus

Accurate identification enables rapid response to limit disease spread. CMV produces distinctive symptoms that become recognizable once you understand the disease's appearance.

Early Symptoms and Initial Recognition

patterns on leaves. There are alternate light and dark green areas on the affected leaves. In some plants, the chlorosis (yellowing) is more pronounced than a sharp mosaic pattern depending on strain CMV and variety of plant.

Normally, first symptoms develop 7 to 10 days after primary infection. Leaf mottling begins on the newest growth, progressively affecting older leaves as the virus moves through the plant's vascular system. The mosaic pattern remains visible throughout the growing season once infection becomes established.

Distinguishing CMV from other mosaic-causing diseases requires careful observation. Other viruses produce different mosaic patterns, so comparing leaf symptoms carefully helps confirm CMV presence. When in doubt, removing the plant and submitting tissue samples to a diagnostic laboratory provides definitive identification.

Advanced Symptoms and Systemic Infection

As CMV infection progresses, plants develop increasingly severe symptoms. Leaves become increasingly distorted and curled, losing normal shape. The entire plant shows stunted growth compared to healthy plants. Photosynthetic capacity decreases dramatically as the virus colonizes all parts of the plant's vascular system.

Flower production declines or ceases entirely on severely infected plants. Even if flowers develop, fruit set becomes extremely poor. The combination of growth stunting and poor reproduction means infected plants produce minimal marketable fruit.

Fruit Symptoms and Marketability Loss

Fruit developing on CMV-infected plants shows severe defects that completely eliminate marketability. Fruit develops warty, bumpy surface characteristics. Deformation causes fruit to grow in twisted, uneven shapes. Discoloration creates patches of lighter or darker skin, making fruit visually unattractive.

As fruit matures, deep cracks develop on the surface. The combination of warty texture, deformation, discoloration, and cracking makes affected fruit completely unmarketable. Most growers discard fruit from infected plants rather than attempting to sell it, representing total economic loss for that portion of production.

Environmental Conditions Favoring CMV Development

Understanding conditions that favor CMV epidemics helps you predict disease risk and time management strategies appropriately.

Warm season conditions dramatically favor CMV spread because aphid activity increases with temperature. Aphid populations explode in warm weather, creating numerous potential vectors for disease transmission. Early summer normally coincides with that period of maximum risk to CMV, when temperatures are high and aphid populations have built up.

The crop is most susceptible at the young fruiting stage. Maximum protection should, therefore, be ensured at this critical growth stage since an early infection reduces production more seriously than a late-season infection. Those plants which do not get infected during the susceptible flowering stage always provide good yield even if they are infected at later stages.

The pressure of the disease, however, is also a function of the seasonal time of planting. Plantings that flower just at or before the peak period of aphid activity are more prone to infection than those either well before or after this peak period. In certain areas, this enables growers to adjust their planting dates as a major practice in minimizing CMV risk.

Prevention Strategies: Your Most Powerful Weapon

Prevention represents your only viable approach for CMV management. Because no chemical cure exists once infection occurs, every action before virus arrives at your plants becomes critical.

Certified Virus-Free Seed and Transplants

Buy your seed from certified companies that maintain strict sanitation controls. Certified seed is tested for freedom from CMV and other pathogens. This is the assurance that your starting material is disease free.

When using transplants, get them from reputable nurseries with a documented virus-free status. A single infected transplant brought into your field can establish CMV in your entire cucumber production area. Verify that transplant producers maintain virus-free mother plants and follow strict sanitation between production beds.

Request virus-free certification documentation when purchasing seed or transplants. Reputable seed companies and nurseries provide this documentation without hesitation. Never use seed or transplants of questionable health status, as the risk of introducing CMV far exceeds any cost savings.

Aphid Vector Management

Managing aphid populations becomes essential for CMV prevention. Reflective mulches (aluminum foil or metallic plastic) disorient and repel aphids, reducing their ability to locate plants. Applying reflective mulch around your cucumber plants creates an inhospitable environment for aphid settlement.

Implement insecticide applications before aphid populations build to damaging levels. Apply insecticides preventively during early season when aphid pressure typically starts. Continue applications on a weekly to biweekly schedule depending on aphid population monitoring. Organic growers can use neem oil, pyrethrum, or other approved botanical insecticides.

Monitor aphid populations using yellow sticky traps and direct field observation. When traps consistently catch aphids or direct observation finds aphids on plants, initiate spray applications immediately. Early action prevents aphid populations from establishing and spreading CMV.

Cultural and Environmental Management

Remove infected plants immediately upon symptom confirmation. Complete removal, including roots and all plant material, prevents continued virus production. Place diseased plants in sealed containers and transport them away from the field to prevent disease spread.

Manage susceptible weeds aggressively because many weeds serve as CMV hosts. Burdock, catnip, flowering spurge, horse nettle, jimsonweed, nightshades, pigweeds, and pokeweeds all harbor CMV. Removing these weeds from field margins and surrounding areas eliminates virus sources that could lead to epidemic development.

Implement crop rotation away from susceptible crops for at least one year. Non-host crops like grains or legumes provide a break in the CMV cycle. Fields planted to non-host crops allow virus populations to decline naturally.

Disinfect tools and equipment between plants using a 10 percent bleach solution. Wash hands between handling multiple plants to prevent mechanical transmission. These simple practices prevent human-mediated spread of CMV from infected to healthy plants.

Resistant and Tolerant Varieties

Growing resistant or tolerant varieties provides your most sustainable long-term CMV management strategy. Resistant varieties bred with CMV resistance genes show minimal symptoms even when exposed to the virus. Some varieties tolerate infection, developing fewer symptoms but maintaining productivity despite infection.

Resistance genes like Cmr1 and cmr2 have been identified and incorporated into some pepper and melon varieties. Cucumber options remain more limited but are improving through ongoing breeding efforts. Consult with seed companies about which varieties show CMV resistance in your region.

Be aware that resistance-breaking variants of CMV emerge over time. Single-gene resistance often breaks within a few years of widespread deployment as the virus evolves. Varieties with multiple resistance genes provide more durable protection than single-gene resistant varieties.

Early Detection and Identification Strategies

Set a routine. Visit the field regularly. This will help in noticing any slight symptoms of CMV long before the disease becomes severe.

Scout the field once every week within the growing season and look for plants with mosaic symptoms. Walk through the planted area systematically and keenly observe the new growth since most probably initial symptoms appear there. Conduct scouting early in the morning when plants are turgid because that is when clear mosaic patterns can best be observed.

If you observe suspicious symptoms, closely examine the affected leaves. Look for its characteristic mosaic pattern of alternating light and dark green areas. Severe infection produces obvious leaf curling and distortion. Document suspected infections with photos and location information for reference.

Distinguish CMV from other mosaic diseases by comparing symptom characteristics. Tomato spotted wilt virus, for example, produces different patterns. When uncertain about disease identification, collect tissue samples and submit them to your extension office or plant diagnostic laboratory for definitive diagnosis.

Remove suspected CMV-infected plants immediately. Do not wait for laboratory confirmation when symptoms are obvious. Every day an infected plant remains in the field allows more aphids to carry the virus to additional plants.

When CMV Infection Occurs: Immediate Response

If CMV symptoms develop on any plants despite your prevention efforts, implement rapid removal protocols.

Remove infected plants completely, including roots and all plant material. Place infected plants in sealed bags or containers to prevent aphid contact and virus escape. Transport infected material away from the field to a location where you can burn or bury it deeply.

Never compost infected plant material in standard compost piles. The virus survives most composting temperatures and can remain viable for extended periods. Composting infected plants creates a source of inoculum that could infect future crops.

Accept that plants showing obvious CMV symptoms cannot be saved. Attempting to treat infected plants wastes time and resources. Remove them quickly to prevent additional spread. Continue aphid management on remaining plants to reduce spread risk.

Document the location and timing of CMV symptoms for future reference. This information guides future management planning and helps identify field areas or management practices associated with CMV development.

Resistant Variety Selection for Long-Term Success

Switching to resistant varieties provides your most sustainable long-term management strategy. Growing varieties naturally resistant to CMV eliminates reliance on intensive spray programs and reduces disease risk across seasons.

Resistance genes like Cmr1 and cmr2 provide different levels of protection against CMV strains. Cmr1, found primarily in pepper varieties, provides strong resistance but covers a narrower range of CMV strains. cmr2 provides resistance to a wider spectrum. Therefore, it will be useful in areas where different strains of CMV exist.

Always test new resistant varieties on part of your field before going into fullscale planting. Test strips can help you determine the performance of the variety under your specific condition-fruit characteristics and apparent tolerance to diseases. This testing reduces risk of committing to varieties that underperform in your area.

Combine variety resistance with other management tactics for the most reliable CMV prevention. Resistant varieties used with certified seed, aphid control, and weed management provide essentially fail-safe CMV management even in high-pressure regions.

Practical Implementation Timeline

Converting knowledge to action requires structured planning throughout the growing season.

Pre-Season Planning (December to February)

Review your past season's CMV history, noting where disease appeared and when symptoms first became visible. Research resistant varieties suitable for your market and production system. Order certified virus-free seed or transplants well in advance.

Contact your extension office to understand CMV risk in your region. Request information about prevalent CMV strains and which varieties show best resistance to local strains.

Early Spring Preparation (March to April)

Order all materials needed for prevention including reflective mulch, insecticides, and monitoring traps. Prepare fields and set up infrastructure. Plan your scouting schedule and establish monitoring protocols.

Early Season Management (May to June)

Use certified virus-free seed and transplants. Reflective mulch if reflective mulch is to be used, install at this time. Set up yellow sticky traps for aphid monitoring. Scout the field as soon as plants emerge on a weekly basis.

Get preventive aphid management underway in good time and on schedule before an assumed build-up of the aphid population. Apply first insecticide applications during early season when plants are most vulnerable.

Mid-Season Monitoring (June to July)

Continue weekly field scouting, focusing on newer growth where CMV symptoms first appear. Maintain aphid monitoring using sticky traps. Adjust spray schedules if aphid populations surge.

Remove any plants showing obvious CMV symptoms immediately. Document the location of infections.

Late Season Management (July to September)

Continue aphid monitoring and management through mid-season. Allow plants to mature and produce fruit. Harvest regularly to remove fruit and reduce plant stress.

Post-Harvest Cleanup (September to November)

Remove all plant material from the field completely. Dispose of infected plant material by burning or burying. Do not compost infected material. Clean equipment thoroughly.

Document all disease observations for next season's planning.

Real-World Case Study and Impact

Understanding CMV's devastating potential demonstrates why prevention matters absolutely.

A vegetable grower in a warm region discovers CMV symptoms on cucumber plants in mid-June. Because no prevention measures were implemented, aphid populations transmitted CMV to susceptible plants. Within two weeks, 40 percent of the cucumber plants show mosaic symptoms. The grower implements emergency aphid control, but the disease has already established. Marketable fruit production drops by 55 percent. The economic loss totals approximately 30,000 dollars.

Contrast this with a proactive grower in the same region who begins with certified virus-free transplants. The grower implements preventive aphid sprays beginning in early season before disease pressure develops. Yellow sticky traps monitor aphid activity, guiding spray timing. Susceptible weeds are removed from field margins. When aphids are detected on sticky traps, the grower applies insecticides immediately. The preventive management program costs approximately 3,000 dollars in materials and labor. The grower experiences zero CMV infection, maintains 95 percent fruit marketability, and generates full expected revenue.

The difference between these scenarios illustrates that prevention costs far less than managing established CMV disease.

Integrating Technology Into Your Management Plan

Modern tools can enhance your CMV management effectiveness. AI-powered plant diagnosis platforms like Plantlyze analyze plant images and provide rapid preliminary assessment of mosaic symptoms. These tools help you distinguish CMV mosaic patterns from other leaf conditions like nutrient deficiency or water stress.

Using Plantlyze, you can photograph suspicious leaves at any time and receive assessment within minutes. This rapid feedback enables faster decision-making and earlier plant removal when CMV appears. When combined with your field observations and aphid monitoring, technology accelerates your response to disease threats.

Visit Plantlyze.com today to access these AI-powered plant care and diagnosis capabilities. The platform helps you identify mosaic virus symptoms with confidence, enabling faster implementation of plant removal and aphid management measures. Early identification transforms CMV management from reactive crop loss into proactive disease prevention.

Key Takeaways For Successful CMV Management

Your cucumber mosaic virus management program must prioritize prevention because no chemical cure exists once infection occurs. First, understand that CMV spreads exclusively through aphid vectors, making aphid control your foundation strategy.

Second, begin with certified virus-free seed and transplants for disease-free starting material. Third, implement preventive aphid management during early season when plants are most vulnerable. Fourth, establish weekly field scouting to detect symptoms early.

Fifth, remove infected plants immediately upon confirmation. Sixth, manage susceptible weeds in field margins and surrounding areas. Seventh, implement crop rotation away from susceptible crops. Eighth, disinfect tools and hands between plant contact.

Ninth, select resistant or tolerant varieties for long-term sustainable management. Tenth, combine multiple prevention tactics for maximum effectiveness. Eleventh, document all observations for future management planning.

Cucumber mosaic virus represents a serious threat, but one you can effectively manage through prevention-focused strategies and early detection. Your successful cucumber harvest depends absolutely on the decisions you make before the season begins regarding virus-free seed selection and aphid management.

References

1. Penn State Extension

Link: https://extension.psu.edu/cucumber-mosaic-virus/

2. Frontiers in Plant Science

Link: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/plant-science/articles/10.3389/fpls.2025.1661085/full

3. NIH/PubMed Central

Link: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7673075/

4. Oxford Academic (Horticulture Research)

Link: https://academic.oup.com/hr/article/12/5/uhaf016/7954091

5. Frontiers in Plant Science

Link: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/plant-science/articles/10.3389/fpls.2018.01106/full